April 1972 – As I walked into the passenger terminal at Yokota Air Base near Tokyo, I was surprised to hear my name being called over the public-address system. I had just arrived by bus after a many hour flight from San Diego into Haneda International Airport.

Haneda is on the far east side of Tokyo and Yokota is well out to the west and the bus was a USAF school bus so it had been yet another long military “no frills” bus ride. This time across Tokyo and on top of a long full flight in American Airlines Economy Class across the Pacific from San Diego so I was dog tired.

I had just completed the two weeks of survival, evasion, resistance and escape/deep water environment survival training (SERE/DWEST), training that would qualify me to fly in the reconnaissance aircraft of Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron ONE (VQ-1), the Navy’s “Spy Squadron” in the Pacific, in hostile airspace and I had no idea why they were calling me. But the message was clear, “LTJG George Guy Thomas, Report to Navy ATCO (Assistance Company).” I had little idea that answering that page would be the start of the most memorable 3 months of my young career…. Indeed, probably of my life.

The ATCO had new orders for me, directing me not to return to my family in Misawa, Japan, 600 miles north of Tokyo, but rather to proceed immediately to the guided missile cruiser USS Worden (DLG-18) in port at Yokosuka Naval Base, nearly 30 miles to the south east, but still in the greater Tokyo, to assume duties as the assistant officer in charge of its Naval Security Group Detachment for a period of up to 2 months. They also provided a phone number to the ship and a point of contact, LT Hugh Doherty, who was a fellow NAVSECGRU officer and a neighbor in Misawa. I was able to get through to him and he told me WORDEN was assigned to conduct a late breaking “special operation,” we might be gone for as long as two months, but probably shorter, and he would tell me more when I got on board.

Hugh and I were trained to run technical intelligence collection operations, so I knew without being told we really could not discuss the details of the operation nor our role in it on that unclear phone circuit. I would learn the details when I reported on board and got to a space (maritime/Navy for ROOM) in the ship cleared for TOP SECRET. In that I had just spent nearly two years training for this type of mission it was not totally unwelcome news…I was a bit distressed to be leaving my wife to care for our 18-month-old child in rural Japan, but Hugh assured me all was well and the other wives of the Direct Support Division would be looking out for them. They had a lot of experience in this as it was their husbands who disappeared for two or more months at a time to run the Navy’s technical collection operations in the north western Pacific and adjacent seas in “direct support” (DirSup) of Naval operations, hence the name of the division.

DirSup had been an integral part of naval operations almost since the advent of radio, really coming into its own during the Navy’s highly effective submarine campaign against the Empire of Japan in World War II, but its operations remained highly classified and never discussed outside of appropriately cleared “spaces.” I was very proud to be joining this tradition of unknown excellence and I grabbed my seabag and jumped on the NAVY shuttle bus headed to Yokosuka, 25 plus miles across Tokyo traffic to the southeast, with no freeways back then. It was a three-hour ride and I was already exhausted but I was so excited to finally get the chance to employ my training that I did not sleep a wink.

Three and a half hours later I was walking up the gangplank of WORDEN. It was both my first ship assignment as a naval officer and as a NavSecGru DirSup officer. I had been on a very similar ship for 20 months as Yeoman, (Navy for clerk) assigned to intelligence duties. For the last five months of the tour on USS HORNE (DLG 30) I had been the de facto Intelligence Officer on the ship and that was what got me selected for the elite NavSecGru, but this was my first time to walk up a ship’s gangplank for duty. I was exhilarated but apprehensive.

I found Hugh’s bunking space and joined him in the wardroom for a cup of coffee and to get a quick brief on what was up. He apologized for my being diverted from going home, but I was not angry at all. This was what I had trained for and I was anxious to get under way on my first assignment. I learned we were going to the Vladivostok operations area (OpArea), home of the Soviet’s Pacific Fleet, to “demonstrate freedom of the seas” and to collect intelligence on the Soviet Navy and any Soviet air units that reacted to us. We had intelligence that units of the Soviet Pacific Fleet were preparing for an operation and our job was to provide early warning of any evidence of hostile intent and to run the intelligence collection operation. Even to this day I cannot discuss in detail what our priority targets were, but the mission had been generated very quickly and we had been placed on board for a very specific purpose. We spent the next two days unpacking our technical intelligence collection equipment and checking it out. This equipment was so classified and expensive that it was not left on warships full time, but rather taken on the ships as they prepared for “special operations.”

On our last night in port Hugh and I had a big dinner at the Yokosuka O’club and came back to the ship about 9 PM to get to bed early as we were getting underway early the next morning. We were to get the ship’s mission brief and introduced to the wardroom, the ship’s officers, as soon as we cleared Tokyo Bay. The crew had seen us as we came back onboard with our equipment, but they were told not to talk to us or speculate out loud as to why we were onboard. This was standard procedure for the DirSup Spooks in those days – may still be, but probably not. There is a great deal more is in the press these days about NSA and signals intelligence (SIGINT), our primary task.

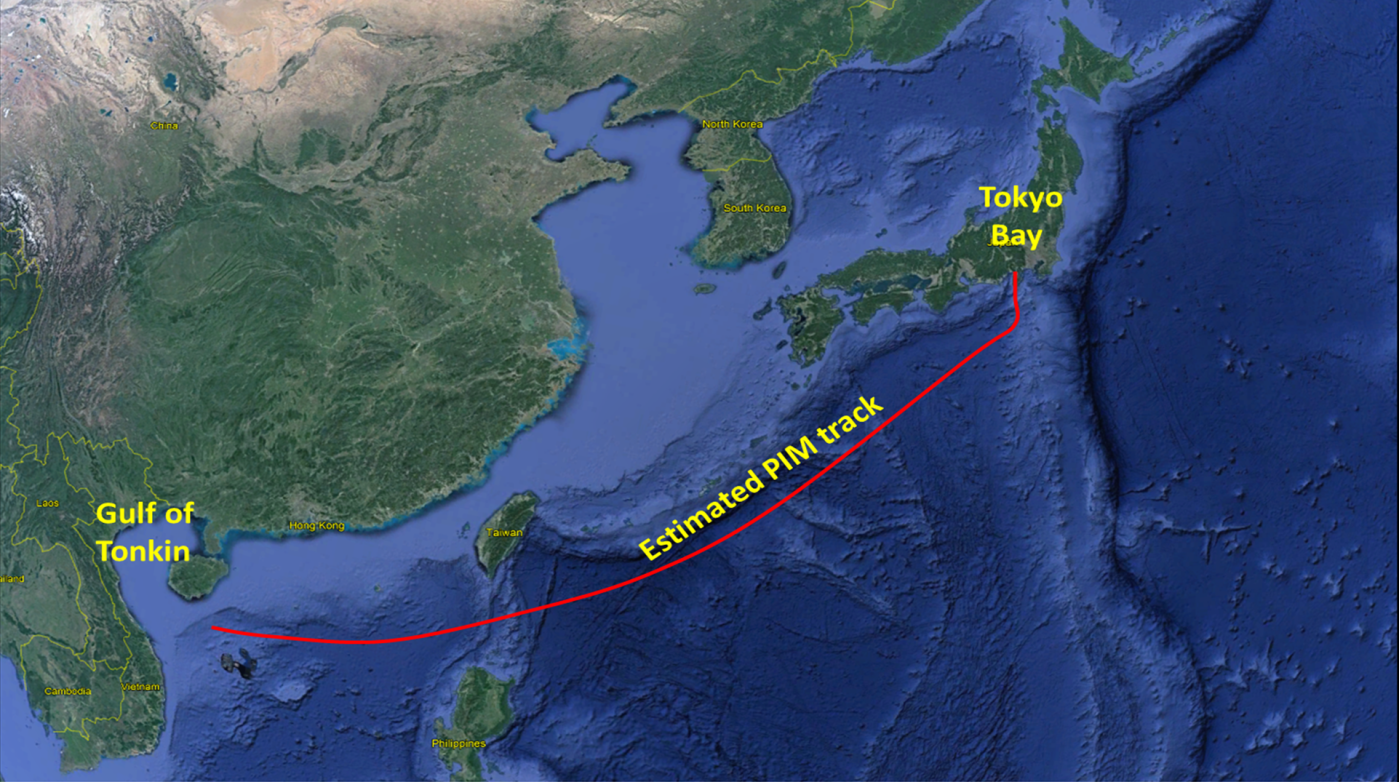

As we arrived back on board that night there was a lot of talk on the ship about the fact that North Vietnam had sent its regular army into South Vietnam in a full-scale invasion, but while we noted the news with professional interest, we basically ignored it. We were going north to the Russian coast, not south to the Gulf of Tonkin, right? The next morning’s brief to all officers changed all of this in a flash. The executive officer, the 2nd in command, briefed the wardroom, the Navy term for all officers of a ship that the main battle army of North Vietnam had invaded South Vietnam the day before and it was possible the war was going to change dramatically and we may be diverted to assist that effort. Hugh and I had, until that moment, naively had not really thought about it much as we knew we were headed to the Russian coast. .Right? Our inexperience in the ways of the Navy deployed in the Western Pacific was showing. An hour later as we headed out into Tokyo Bay and cleared the Yokosuka sea buoy marking the entrance to that naval base CAPT George Shick, WORDEN’s commanding officer, came on the 1MC, the ship’s generally announcing system, and informed the crew that our orders had indeed changed and we were turning south, not north, and proceeding to the northern Gulf of Tonkin at best speed to assist in the largest build-up of naval forces since the landing at Inchon in the Korean War nearly 20 years before.

We were to assist in the aerial and naval bombardment of North Vietnam and its army in South Vietnam. Hugh and I looked at each other in surprise and shock. Our expensive technical intelligence collection equipment was optimized for the targets in the Sea of Japan, and much of it would be useless in the Gulf of Tonkin. Also, our team was made up of area specialists for the Northwest Pacific, not the Gulf of Tonkin. Indeed, apart from one E-8 marine communications specialist, I was the only member of our team who had been to Vietnam. We had been shanghaied!

During my short time onboard, I had learned that WORDEN was undermanned with junior officers and needed qualified combat-information-center (CIC) watch officers and officers of the deck. I had spent nearly two years on a very similar ship, HORNE, much of it on the bridge or fantail as a phone talker. I had also spent almost six months as the acting intelligence officer, standing watches port & starboard watched in CIC. 12 hours on, 12 hours off, but on-call 24/7 and while off the coast of North Vietnam it was more like 18 hours on, 6 off if that much, so I was very familiar with the equipment in CIC. Both on HORNE and before that as a Sea Scout, I studied how to be an Officer of the Deck (OOD), hoping to be one someday, a goal that I had put on the back burner as I learned how to be a “spook”, a technical intelligence officer. Even though a junior enlisted man on HORNE I also studied how to use every piece of equipment in CIC, especially the WLR-1, ULQ-6 and ALR-91 electronic warfare equipment, which absolutely fascinated me. I had also learned how to use the several radars, and the computer systems running the Navy Tactical Data System. I was no expert, but I did understand them completely and I had no doubt I could, with that background, assist the ship both on the bridge and in CIC. It certainly beat sitting in the officers’ mess drinking coffee day in/day out and our intelligence collection spaces were much too small for just sitting around.

I thought about it for the morning but by lunch I knew what I wanted to do. I went to Hugh and asked his permission to volunteer to stand ship’s watches. He was doubtful they would let me do it. But he had no real idea how much direct, pertinent experience I already had, even though I was a just LTJG. He was going to spend his time training the team to become better systems operators and analysts, but there was a little room anywhere on the ship to discuss highly classified matters, and technical intelligence was even more highly classified then today. He was probably happy I had found something to do, and I could train with the team when I was not on watch.

I sought out the senior watch officer, the officer responsible for manning the bridge and CIC with qualified officers and offered my assistance. We talked briefly and I laid out my experience and interest in a naval career. In those days a lot of junior officers were in the Navy to avoid the draft, but I wanted to assure him I was not one of those. We both knew that qualifying as an OOD could not hurt, indeed, it might even be a “tie-breaker” for a promotion sometime in the future, and besides I was truly interested. We went to CIC and he asked me to describe the purpose of everything I saw there, which I did. He remarked he wished his other LTJGs were as checked out as I was. And we went to the bridge, where again he tested my knowledge. I easily passed. He was glad to have to have another qualified officer for his watch list. We both knew I needed to be trained in how WORDEN did things and he quickly outlined a three day training program to bring me up to speed.

My first watch under instruction was in CIC and over the period of that first watch I demonstrated to the watch team that I knew the systems and how to use them, cold. I had not wasted my time on HORNE, even if I was just an YN3, a junior petty officer. My next several watches were shifted to the bridge where I needed more training, but was able to qualify as a Junior Officer of the Deck in less than 3 days, which the LCDR senior watch officer said was record time for a junior officer in his experience (I did have a running start!) and scheduled me to stand my first full watch not under instruction commencing 0345 16 April 1972. It was a fateful time to be assuming the watch as many miles away, in Washington DC, the decision had been made to commence using B-52s against the Haiphong, North Vietnam’s major port, at 0355 on that day, 10 minutes after I assumed the watch.

At SERE/DWEST, I had not shaved for several days and had liked the red fuzz that sprung up. I almost kept it, but had decided to shave it off. As I dressed for my first at sea watch as a naval officer I again considered growing a beard and decided for it. That decision got me on the bridge a few minutes early and that timing proved critical and may well have saved my life. Prior to assuming the watch on the bridge all officers are routinely required to visit CIC to get a situation update. I dutifully visited CIC as I had been trained to do, but there the situation was anything but routine. I had not been told of the impending B-52 strike the night before and did not know we were going to be as close to the harbor as originally planned. I learned we had moved well north of where we had been operating in the north central portion of the Gulf of Tonkin and were now very close to Haiphong. WORDEN was going north to position its SAR helo, who could only hold 2 or 3 passengers due to its being heavily armored, to be able to make multiple short runs to pick up the eight man crew of any B-52 that was downed over the harbor. My first watch promised to be anything but routine. We were all pretty excited to be participating in history and would probably have a ringside seat to the real action…Little did we know…

One other short brief was of particular significance. ELINT (Electronic intelligence) had detected a brief intercept of the radar associated with North Vietnamese PT boats. It could also be the radar on a Chinese or Korean submarine, but none were known to be in the area and it was deemed highly unlikely a submarine would be operating in this area, and if it was, it was even more unlikely it would be operating its radar. Still, it did make us think and the several watch teams (sonar, radar, ASW torpedo, guns, and missile) we were all at full alert, but still not fully manned. This was also true of our damage control teams. We were in full EMCON, not radiating anything, which was usual when you are that close to a hostile coast. Once you are discovered there is little reason to not radiate, but we were hoping we had not been detected. We were watching the tactical situation over NTDS. Our radar screens were being updated by other ships in the task force and their data was being data-linked to us.

28 March 2021 at 14:54

Can’t wait for the next installment.

LikeLike

28 March 2021 at 15:59

The canceled mission to the North of Japan sounds more like national tasking than DIRSUP.

LikeLike

29 March 2021 at 16:36

He’s got me hooked. Looking forward to the rest of the story.

LikeLike

31 March 2021 at 22:08

I sailed on the horne in 70 and on 2 other ships but never carried a cta branch.

LikeLike