By Bud Beck

It all began at Wahiawa in the later part of 1944 when section 3 reported to op 4 for the eve watch. The memorandum on the bulletin board glared “Volunteers needed for Island ‘X’ – sign up below” The memo was originated by CRE Schmelzer, The Pacific HF/DF Net Control Officer. It was common knowledge that Iwo Jima was the designated Island “X.” Missing at that time was a better understanding of the word “Volunteer.” CRE Schmelzer was to be OIC of Station X, but was later replaced by LTJG William Bobek. Iwo Jima was designated Station “AN.” When the USN station number system was initiated, the station designator was changed to USN 505. The list filled up fast and sixteen volunteers and the OIC were selected. They included:

Beck, Richard P.. RM2 (Somebody gave me the name “Spanky”)

Bobek, William LTJG OIC

Boyd, Charles A. RM1

Brubaker, Roy E. RM2 (Red was from Berkeley)

Callahan, Daniel P. RM1 (Danny Dingle)

Casey, William T. RM2

Chandler, Robert E. RM2

Deboer, John D. (better known as “PP”)

Fabiszak, William F. RM2 (FABU)

Harkness, Robert L. RM3 (Harko)

Johnson, Thomas D. RM2 (went by Dale)

Jones, James W. RMC (Everybody knew him as 5-0 Jones)

McArthur, James RM1

Naugle, David K. RM1 (When Dave spoke, you knew he was from Texas)

Reed, Neil M. RM2

Suggs, Wallace C. RM2 (Wally was from Green River, Wyoming)

Syx, Richard Leo RM1

Smokey, the dog belonging to J. W. Jones, also volunteered.

After being relieved of watch, we spent the next few months accumulating station equipment and making it ready for packing and shipping. This included receivers, transmitters, and all the odds and ends needed to set up an intercept and HF/DF Station from scratch.

Iwo Jima was originally developed as a Direction Finding (D/F) activity. With the advent of Victory in Europe (VE), more intercept personnel became available. They were sent to Bainbridge Island for Orange [Japanese] training, and out into the Pacific areas for assignment.

The original D/F concept for Iwo Jima was amended to include search and intercept positions and the necessary receivers and RIPs [Japanese Morse keyboard typewriters] were included in the inventory. The prime HF/DF equipment was a model DAW-1 mobile D/F unit, a model DP-15, and a DAB-3 D/F unit. The DAW-1 consisted of a truck and trailer with a model DAQ D/F unit, a TCS-9 transmitter and receiver, and a coffee pot – all powered by the noisiest Onan generator available. I say noisy because when we stood watches alone, in the middle of the beach, that generator could be heard for hundreds of miles.

The DAW-1 was set up in the Pineapple fields of Wahiawa near the CXK for testing and limited participation in the HF/DF net activities. This provided us with valuable training and experience in the operation of the DAQ. The DAQ displayed a propeller shaped image similar to that of the DAJ. The DAW-1 was operationally self-contained, as one operator could work the flash and reporting circuits in addition to taking bearings. We used the call sign NIT-1.

NSD Pearl assigned Station X a small warehouse building for storage and packing our gear prior to shipment. In addition to packing and crating material, we were given several fork lifts for handling the heavy crates. We soon became experts in the art of packing and crating to meet advanced base requirements. The station was assigned the shipping designator “URIK -96.” URIK for Iwo Jima and 96 for the Supplementary Radio Station. The fork lifts were used primarily for racing around the warehouse.

Now was the time for our advanced base training. This is where they hoped to teach a disparate group of radio operators how to take care of themselves in an advanced theater of operations. They issued us 30 cal. carbines and taught us how take them apart, clean, oil, re-assemble, and fire them.. Other instructions included advanced base sanitation. We learned how to build, maintain and use the two section latrine and how to properly use and maintain our mess gear. Their motto was “Watch the flies as they will cause you run.” After that, were issued green uniforms, mosquito nets, tents, cots, and all other gear needed to exist in a forward area. They all laughed when I pilfered a set of bunk springs and carried them with me to Iwo. But guess who was the only one to sleep on a decent bunk while all others (including the OIC) slept on lumpy army cots.

Finally we were all trained, packed, inoculated, lectured and eager to go. Our equipment was assigned to the fourth echelon and loaded aboard The SS Nancy Hanks at Iroquois Point, Pearl Harbor on the 28th of February. Brubaker and Harkness were volunteered to ride the SS Nancy Hanks to keep an eye on our classified gear. They were also given custody of Smokey. The rest of us (except Boyd and McArthur,) boarded the MS Bosch Fontein at Pearl Harbor on the 4th of March. The Bosch Fontein was of Dutch registry with a Dutch crew and lots of wooden decks, rails and doors. There was an American Armed Guard aboard. Boyd and McArthur were to accompany LTJG Bobek and fly on ahead to assist and facilitate the arrival of the gear and remaining crew.

Something happened and we beat them out there. Only LTJG Bobek was there to greet us when we splashed ashore.

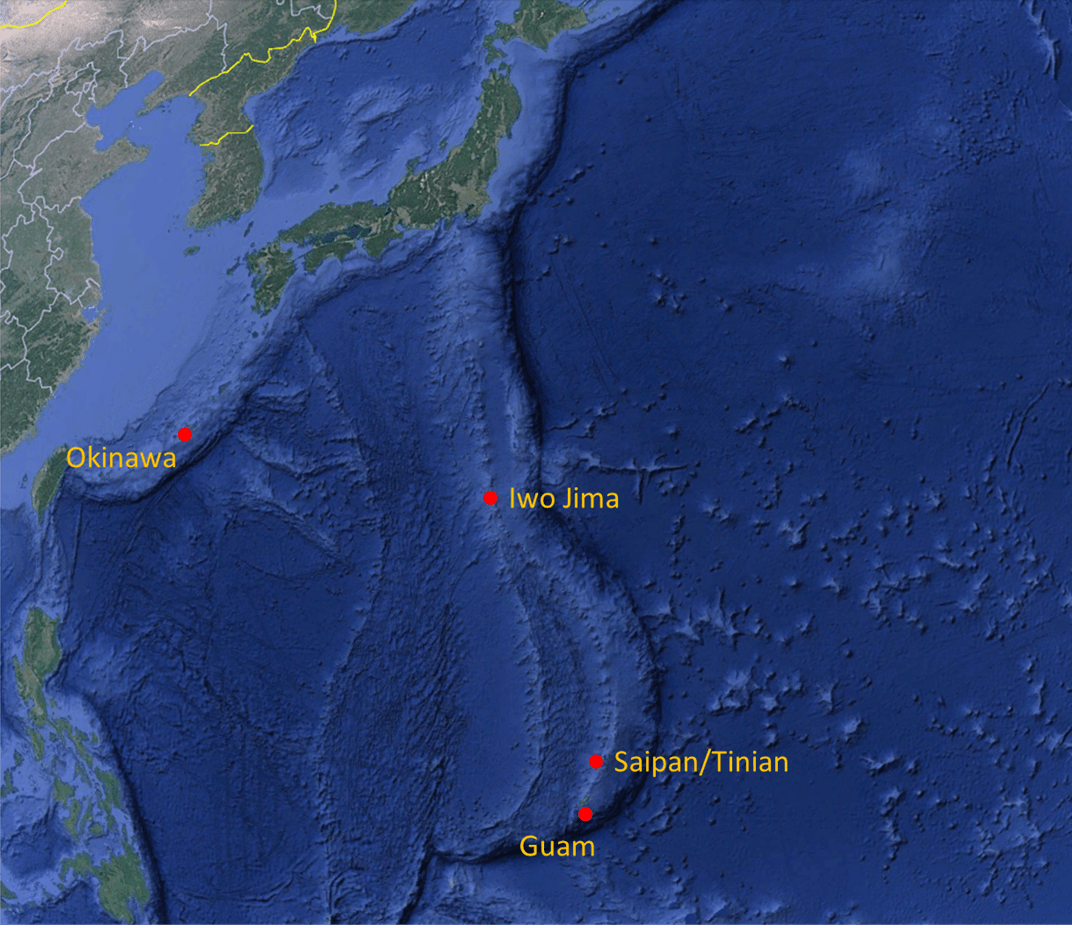

The 4 week trip from Pearl to Iwo Jima was non-exciting, to say the least. When the Bosch Fontein left San Francisco, she had a BB and a DD for an escort. She joined the Nancy Hanks for a convoy of two and we had a DD escort to Kwajalein, and a DE escort to Eniwetok, and Saipan. From Saipan to Iwo Jima, we had a PC (Patrol craft.) I suspect if we had gone any further, we would have had a row boat with a BB gun for an escort.

As radiomen, we were assigned to assist the only signalman onboard. The Bosch Fontein carried a complete Army Hospital onboard. The chow lines were long, fresh air space on the open weather deck was limited, and ships company had reserved seats at the movies. We considered standing watches with the ships company a great improvement over troop status, as it gave us the same privileges. We stood watches on the signal bridge, re-learning the signal flags and the semaphore, operating the TBS Transceiver (with a five mile range) to maintain radio contact with the convoy, and in general, had a ball. Being a small craft, the escort was not always visible, especially in 10 foot waves.

We arrived safe and sound at Iwo Jima on the 2nd of April, but didn’t go ashore till the 5th of April. Each day, the Dutch Captain would get braver and inch closer to the beach. We were fascinated by the fireworks on the island. Tracers, trip flares, continuing flashes and an occasional “”plink” on the ships. We didn’t realize how dangerous it was to watch a tracer that seemed to be standing still. Finally, it was our turn and we were loaded on a landing craft and taken to the beach. The only secure landing area was on the south end of the island at the foot of Mt. Surabachi. The surf was rough and scary and the landing craft swamped just as we were unloading. Our seabags and tutus were soaked. Welcome to Iwo Jima.

Iwo Jima is a pear shaped island about 5 miles long and 1 mile wide. The sand on the beaches was black due to the active volcano, Mt. Surabatchi. The center of the island was mostly hard-pan clay. This clay was scooped from all over the island to construct landing strips for B-29s, Army Air Force P-51 Mustangs and P-47 Thunderbolts. A few sulfur pits with their rotten egg smell dotted the island. The only flat, sandy beach on the entire island was assigned to the Supplementary Radio Station due to the nature of our work and the need for wide open spaces for our HF/DF antennas. We were under the operational command of FRUPAC and GROPAC 11 provided administrative support.

LTJG Bobek was there to greet us led us to our station location – if you could call it that. The entire area was occupied by the 90th Construction Battalion, and they were not about to move. We tolerated them because there were more of them and besides, they were going to build our operations building, the DAB shack, and set up the antenna poles. We were told to find a place inside the BAR perimeter and make-do the best we could. After the operations building (one half of a Quonset hut), was completed, the CB’s moved to another location and we were on our own. Although the island was called secure, we were treated to several Banzai raids.

The marines, and later the Army were forever opening up Japanese caves and routing out stragglers. To make matters worse, they built a POW camp next to our station. Our air raid shelters were used on numerous occasions.

Boyd and McAurthur arrived on the 6th of April. They had been waiting on Guam for air transportation.

On the 14th of April, sixteen additional personnel reported for duty. Most of these people came from Brazil, and were unknown to us as they had worked on the Atlanic problem. I wish I could remember all their names, but there was Holden, Killian, Pinky Higgins, Abrams and Benton. Russ Fisher reported in July. The station ended up with 41 enlisted and 3 officers.

All hands pitched in and worked long hours day and night to set up the station. First priority was to fire up the generator and unpack equipment to rig antennas, wire the shack to set up positions, and get the station operational.. The DAW-1 was the first piece of equipment to become operational, and on the 11th of April, NBR reported to NIM, net control on Guam and went on a 3 section watch. The station could not fully participate in the HF/DF net until the 16th of April when Guam shipped our cryptographic material. The remaining personnel continued construction of the station. High on the list was the construction of an air raid shelter, a permanent potty, and installation of the DAB-3 and DP-15 direction finders. At this time, a power cable was laid out to the DAW, eliminating the need for the noisy Onan generator. The flash and reporting circuits were moved into the operations shack.

Once again, the 90th Construction battalion “CBs” appeared and erected several Quonset huts for our permanent living quarters. The tents left a lot to be desired.

The entire station site was covered with debris of all kind and the metal objects like old anchor chains were affecting the bearings. This necessitated an immediate clean-up of the entire area around the DF units. Speaking of bearings, for some strange reason, the RCA built DAQ-1 was not capable of able or baker bearings. Comes now 5-0 Jones who disconnected the factory grounding system, and strung radials in a 360 degree circle from the antenna base. (see photo) After a series of check bearings, we were able to get solid readings we could rely on.

During the clean-up of the station, we came across several concrete cylinders similar to sewer lines. 5-0 Jones, in all his wisdom, concluded the cylinders were part of a Japanese well that was destroyed during the pre-landing bombardments. A lot of digging, proved he was right. We rebuilt the well and soon was pumping up water that was 170 degrees. The hot water was the result of the active volcano on Iwo Jima. The water was not potable as it had a sulfur content. But it was great for showers and washing clothes. In the beginning, the water was hauled up in buckets. Later on, an electric fuel pump was salvaged from a junked B-29 and proved more than adequate for our purposes. We pilfered a few P-51 wing tanks and rigged them for water storage and showers. Water pumped up in the morning would be cool enough to use in the evening. We were thankful for the showers. Especially after the long, dusty trip over to the mess tent.

In addition to the HF/DF activities, the station eventually established 7 search and intercept positions, and some UHF activities most of us were not privy to. I do not recall our coverage assignments, but we originated a lot of “SA TE KO 4” flashes on 6390 to net control. Big smiles always surfaced when a Japanese unit would transmit “HI HI HI,” which was Japanese for “Hey TOJO, somebody found us and are shooting at us.” We settled into a three section watch with working parties galore. We also participated in the AIR/SEA rescue operation nicked named “DUMBO.” This operation provided surface and submarine pickets every 25 miles between The Marianas and Japan. Their mission was to rescue fliers whose planes went down at sea. Our participation was to provide DF bearings on crippled planes and assist their operations in guiding them to safety. A direct phone link between the DAW and the Flight Operations Center provided immediate emergency assistance to planes in distress. Many times the station received the gratitude (bottled spirits included) of the flight center. This was a very rewarding experience to assist in an AIR/SEA rescue.

An interesting side note concerning our station on Iwo Jima appeared on the Discovery (cable) Channel. They have a series called “WINGS” and one program is devoted to B-29’s and included their use of Iwo Jima as an emergency landing field. One segment follows a disabled B-29 as it crash-lands in the water off from our station. As the camera follows the plane, it passes through our station. You can see the operations shack, the antenna poles, and as the plane comes to rest, there, right in the middle of the picture is the DAB shack.

GROPAC 11 provided sentries to our activity for physical security. They soon became part of our family (not in the classified areas) and after their watch, would take a shower, wash their clothes and find an empty bunk. The only time they went back to the naval station was for chow and pay days. Near our station, The Navy constructed several large elephant huts for their supply depot. To show their appreciation for this arrangement, the sentries arranged for a piece of corrugated tin on an elephant hut that stored beer to be loosened. I had better quit here.

Our biggest thrill came when, if memory serves me correctly, Bill Casey was passing idle time by copying JAP/JUP, the Japanese English Language propaganda broadcast. Unaware of the text, he copied the announcement that “Japan was willing to accept the Potsdam proclamation providing they could keep their Emperor,” or words to that effect. (The Potsdam proclamation called for Japan to surrender unconditionally.) This message was copied after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although he denied it, we all accused him of making up the copy for this was too good to be true. All hands along with every spare receiver and mill were used to copy the next broadcast. Needless to say, we were overly excited. Everybody was wide awake at this time and decided to go to mid-rats. Naturally, we told anybody we met about the announcement. The news spread fast because the Island Commander called LT. Bobek at 0200 to find out who was responsible for starting an unconfirmed rumor. OOPS! We forgot to wake LT. Bobek and tell him. Several trips were made to the beer hut that night.

The surrender documents the Japanese signed included a ban on encryption and sharp reduction in their military radio communications. Our assignments were reduced, and soon, there was very little need for station “AN.” We began the happy task of decommissioning the station and the first drafts of personnel were sent for re-assignment or discharge. It was a happy day when we left Iwo Jima and headed home. Chief Jones ended up as Radioman-in-Charge for the final task of closing the station.

Some of this information comes from memory and most from official documents.

2 January 2026 at 07:00

Thanks Mario, I knew Danny Callahan, known as Danny Dingle very well. Did duty with him at Comm Unit 35, Yokosuka, Bremerhaven and Meade. Great guy, one of a kind.

LikeLike