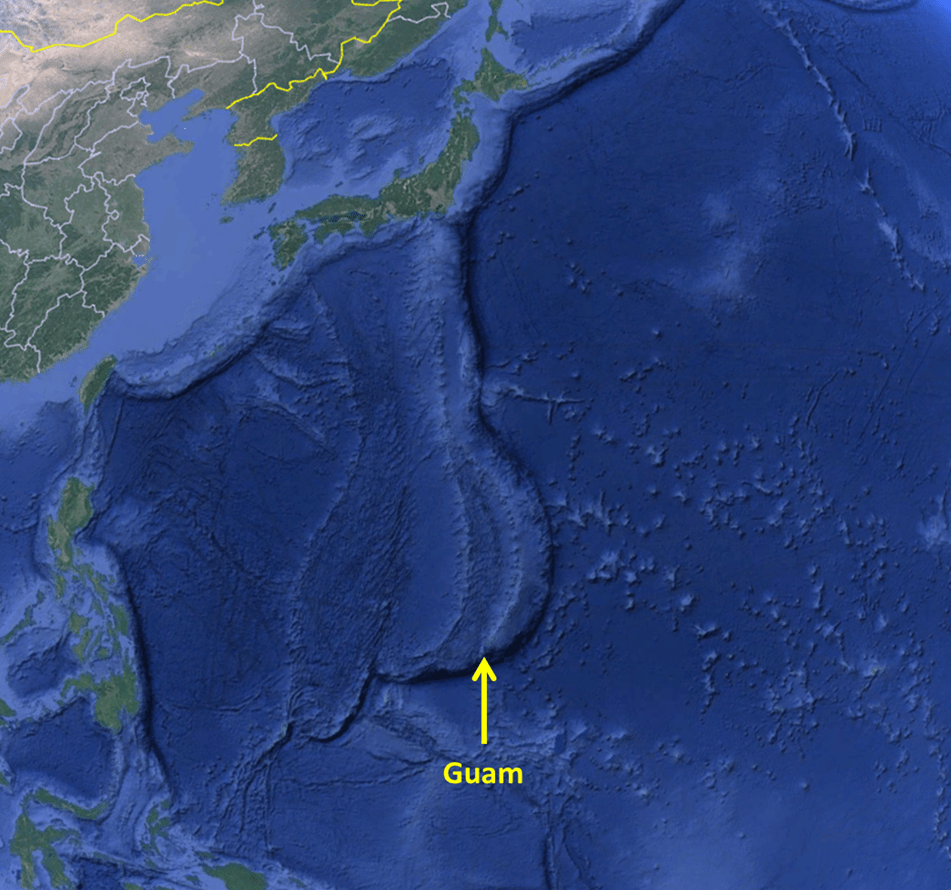

The history of communication intelligence (COMINT) operations on Guam began in March 1929 with the establishment of a one-man intercept station. The first operator arrived from the recently closed Shanghai intercept site. Although the Navy Security Group (NSG) had planned to establish a station on Guam as early as June 23, 1926, those plans were never implemented, and a 1928 outline of a proposed wartime COMINT network made no mention of the island.

The initial intercept facility was set up in Building 62 on the palace grounds of the U.S. Naval Station in Agana, later relocated to Building 84 between December 20, 1932, and January 5, 1933. The unit’s manpower grew with the arrival of seven graduates from the Navy’s first radio intelligence training program in Washington, D.C.—the renowned On-the-Roof Gang. The Guam station achieved notable success during Japanese fleet maneuvers in 1929 and 1930, earning a commendation from the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) on March 5, 1932, for its diligence and initiative.

Despite this recognition, budget constraints in 1932 may have forced the CNO to reduce Guam’s operations to a minimum, shifting much of its coverage to Hawaii. However, this reduction likely never occurred, given the commendation and continued activity that followed.

Relocation and Expansion (1933–1941)

In 1933 or 1934, the intercept site was moved from the Naval Station to an abandoned tuberculosis hospital on a hill outside Agana, where it remained until its eventual relocation to Libugon. Following an inspection by the Commander-in-Chief, Asiatic Fleet on October 11, 1934, it was recommended that the facility be transferred to an abandoned Navy radio station at Libugon, located four miles from Agana.

The Libugon site had been established in 1917 as part of the Navy’s Trans-Pacific High Power (Arc) communications circuit. A low-power high-frequency transmitter was added in 1927, but the site was closed in March 1932 as a cost-saving measure. The intercept facility was officially transferred from Agana to Libugon on October 11, 1934, where it operated until 1941, when it was captured by Japanese forces during the opening phase of World War II.

In 1935, the Bureau of Engineering proposed relocating the intercept site back to Agana to reduce costs, but the CNO intervened, affirming Guam’s growing importance in the Navy’s expanding COMINT network.

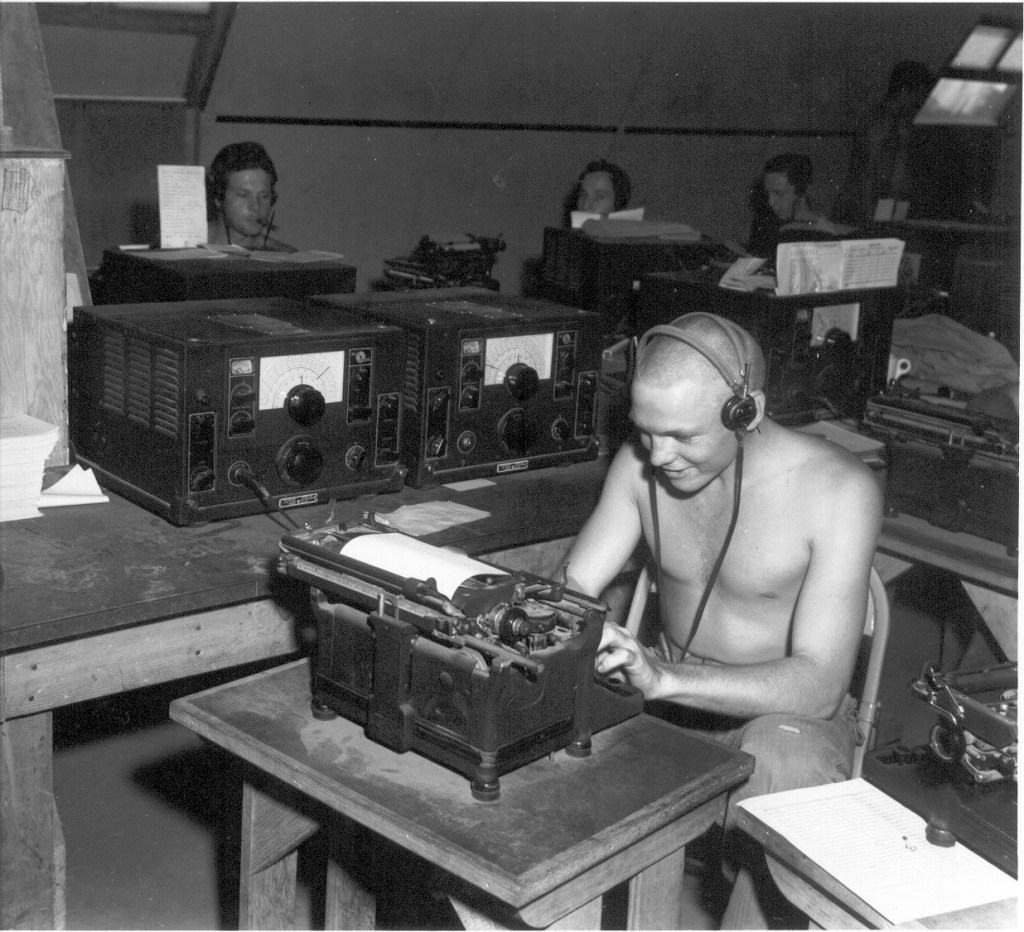

During this period, Guam’s intercept equipment was largely composed of obsolete or surplus gear from other stations such as Cavite. The USS Gold Star (AK-12) delivered an RF receiver in October 1934, three Kana typewriters (RIP-5) in December 1936, and recording equipment in March 1938.

By 1940, personnel strength had increased to ten men, with a request for four additional billets denied in January 1940. As the U.S. approached World War II, Station B operated with just eight personnel, led by Chief Radioman (CRM) D. W. Barnum, who relieved CRM J. W. Pearson on September 21, 1941. RM2 D. L. McCune reported for duty the following month.

Capture and Destruction of Materials (1941)

On December 4, 1941, the Office of Naval Operations (OPNAV) ordered the destruction of all classified materials except those essential to operations. According to wartime records, contact with Guam was lost on December 8, 1941, and all eight intercept operators were taken prisoner by Japanese forces. A postwar memorandum from OP-20G commended the crew for successfully destroying all classified material before capture.

Personnel at the time of capture were:

CRM D. W. Barnum – Radioman-in-Charge

RM1 M. T. Smith (advanced to CRM, papers not yet received)

RM1 R. R. Ellis

RM2 S. T. Faulkner

RM2 E. J. Dullard

RM2 R. G. Parr

RM2 H. E. Joslin

RM2 D. L. McCune

Direction-Finding Development

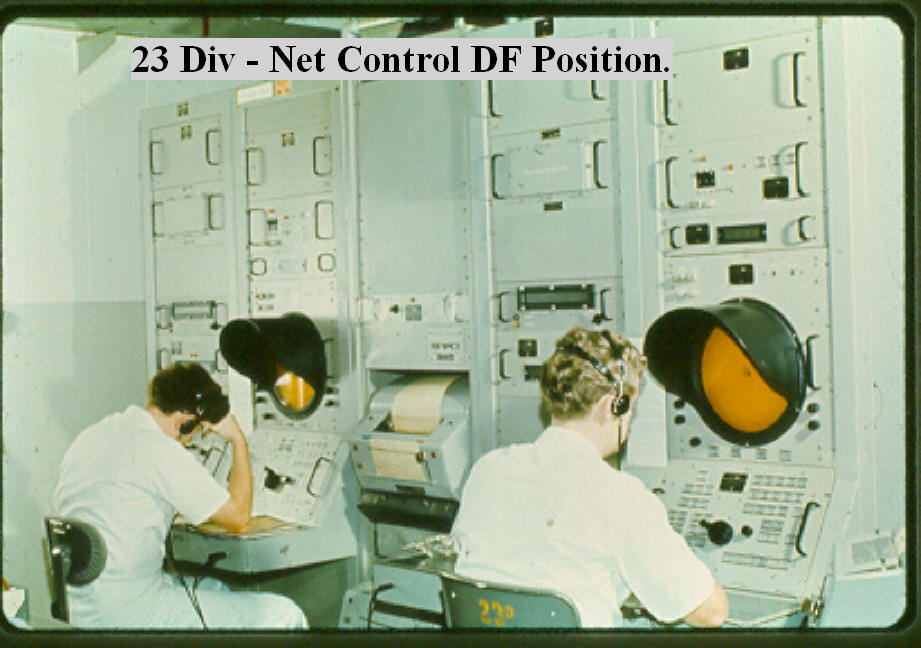

Requests to install direction-finding (DF) equipment on Guam date back to June 22, 1935. Although initial site inspections were conducted the following month, little progress was made until 1937, when an XAB-RAB-2 rotating Adcock-type HFDF system—developed by the Naval Research Laboratory—was shipped to Guam. Commissioned in July 1937, it became the Navy’s second intelligence DF site, following Cavite in the Philippines.

A newer Gordon Adcock rotating antenna (DT) arrived aboard USS Chaumont (AP-5) on October 18, 1938, replacing the earlier XAB-RAB-2 system, which was returned to Cavite via USS Canopus (AS-5).

A powerful typhoon on November 3, 1940, destroyed the DT system, but Guam quickly recovered. Replacement DF systems (models DT, DR, and later DY-1) arrived from Shanghai and were operational by late 1940, with full installation completed in mid-1941.

Chief Radiomen-in-Charge, Station B:

CRM J. Goldstein – Oct 1929 – ?

CRM M. W. Hyon – Jun 1932 – ?

CRM Antone Novack – Jan 1938 – Jul 1939

CRM J. W. Pearson – Jul 1939 – Sep 21, 1941

CRM D. W. Barnum – Sep 21, 1941 – Dec 1941

Post–World War II Developments

Following World War II, Guam underwent extensive reconstruction. The capital city, Agana, had been completely destroyed during the conflict. From 1944 to 1949, U.S. naval officers serving as Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Marianas (COMNAVMARIANAS) also held administrative duties as governors of Guam and nearby Pacific territories.

The Organic Act of Guam, enacted on August 1, 1950, transferred the island’s administration from the U.S. Navy to the Department of the Interior, designating Guam as an unincorporated U.S. territory. The island also became the headquarters for the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

From 1944 to March 29, 1952, Naval Station Guam functioned as a Naval Operations Base (NOB) providing full fleet support. In September 1956, the base was disestablished and reassigned under the military command of COMNAVMARIANAS.

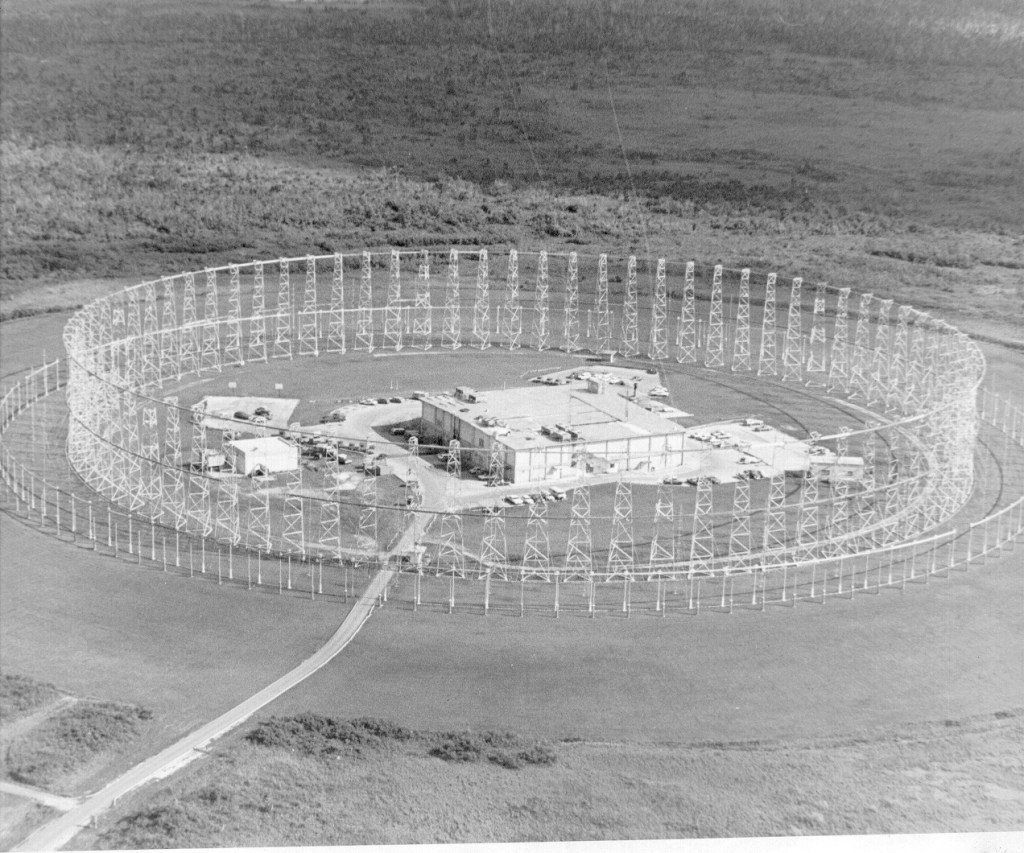

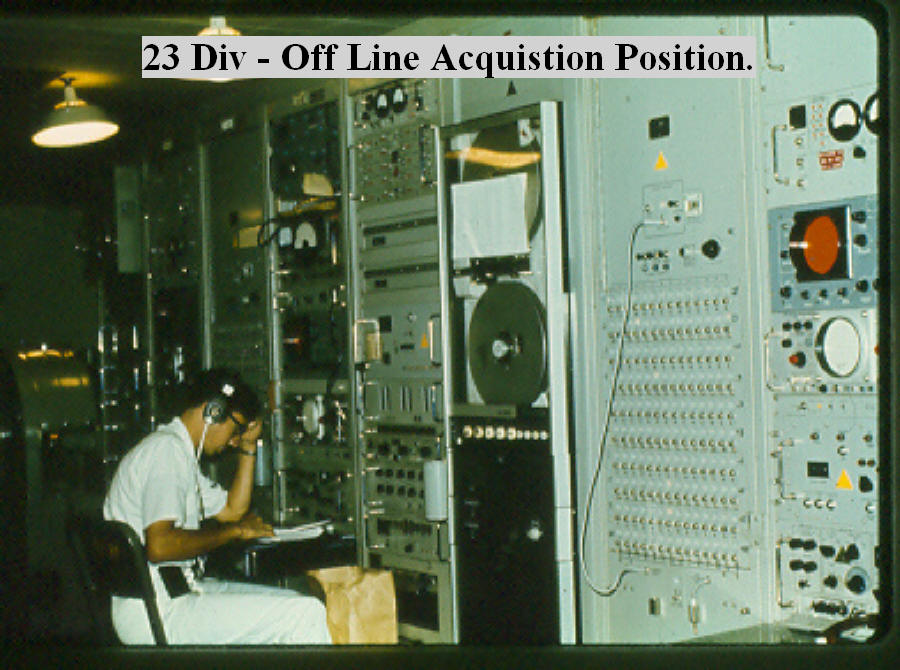

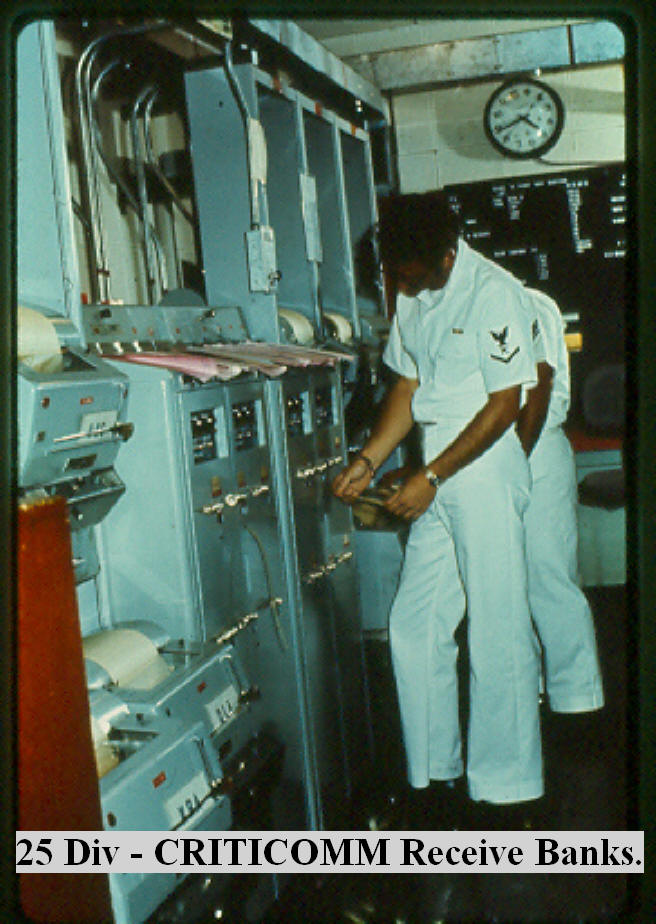

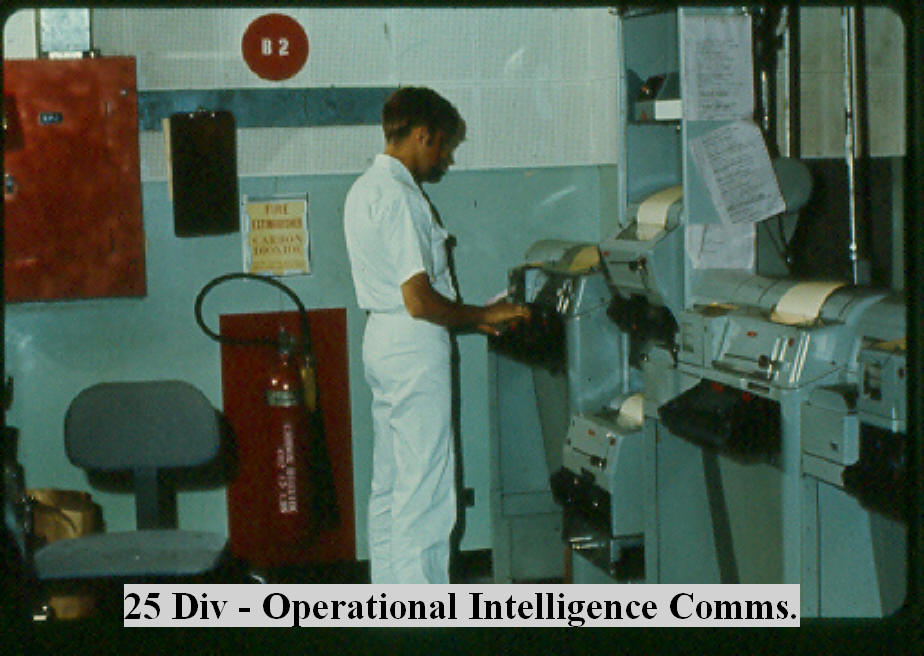

In 1954, the Naval Communications Station (NCS) Finnegayan was established. Formerly known as Station Able and COMSEC Unit #701, it was redesignated as the Naval Security Group Department, NCS Finnegayan. The facility operated a high-frequency direction-finding (HFDF) network and provided communication and cryptologic support to the Navy and other Department of Defense entities.

Its signature feature was a massive AN/FRD-10A Circularly Disposed Antenna Array (CDAA)—commonly called a Wullenweber antenna. The system ceased operations on December 31, 1999, and remains abandoned on the grounds of NAVCOMTELSTA Guam, a reminder of the island’s enduring legacy in naval intelligence history.

Sources:

NCVA

navycthistory.com/

cnic.navy.mil/regions/jrm/installations/navbase_guam/about/history.html (no longer valid)

31 December 2025 at 08:21

i was assigned to COMSEC 701 from 1967-1968. Div Off was Ens Finnenbock, Div CPO was CTC Cliff Fergusson, CT1 Bill Heinike (sp) was LPO.

Bill Carter

LikeLike

31 December 2025 at 10:53

No mention of RM2 Tweed, who evaded the Japanese until 1944 when the US forces retook the Island. Was he in another activity on Guam?

LikeLike

31 December 2025 at 17:08

When arriving on Island in early ’72…was told by a Chief…”everything here will rust in the humidity, including your toenails!”…and, “oh by the way…”they” just took off a Japanese soldier (Sgt. Soichi Youkoi??? no way am I going to be able to spell that) who’d been hiding on the island since WWII a few months ago.” For several more weeks, I guess they’d circle the island with bullhorns trying to see if anyone else was out there to surrender as he’d said he was one of three that separated yrs. ago so as to NOT be able to lead anyone to others if captured. This took place before I arrived as well.

Over the course of the first few months, I got certified for scuba diving while on base. Having purchased a ’63 Rambler station wagon, often, I’d be the one to drive a bunch of fellow divers out to some place and we’d either dive nearby of hike the shore until we’d decide to find out what was out there. In one instance, one of the guys I dove with was an A brancher who was about 5’2 or 3? We headed out to snorkel the area first and then headed back to pick up our tanks and do a dive after eating. When we got ashore, he went to his towel and couldn’t find his pants and shirt! We had cameras and diving tanks as well as other “stuff” on the beach, but only his stuff was missing. It didn’t take us long to consider the possibility that some other Japanese soldier holdout may have come across our stuff and only his fit. The locals had no desire to take Navy dungarees and would’ve more likely “borrowed” the camera gear for an “undetermined time.” I think we still decided to dive afterwords, but don’t remember ever going back to that area. As it was, I don’t know if anyone of the 4 us even mentioned what had occurred to anyone else when we got back to base…such is the fickleness of youth.

Over the course of the remainder of my “time” left on the island…this was the only time anything went “missing” in all the remaining dives taken…and we took at least one-two every “off duty” period for at least a yr.

LikeLike