The Americans’ spirits lifted on March 17, 1968 when Steve Woelk, the young fireman injured by the same shell that killed Duane Hodges, was reunited with them. Since the day of their capture, Woelk had been kept in a North Korean hospital, and despite numerous inquiries, Bucher had received almost no information about his condition. An upbeat Kansan known for his country-western singing, Woelk was well liked by his shipmates, and Bucher and the officers warmly greeted him as he hobbled through the front door of the “Country Club,” (prison) as the men had dubbed their new prison.

Woelk’s account of his medical treatment sounded like something from a horror novel. When the shell exploded, he was thrown backward but managed to crawl to the relative safety of the wardroom. A jagged metal fragment had torn into his upper right thigh, ripped through his abdomen, and exited through his right buttock. One testicle had been shattered, and shrapnel had sheared off two inches of his tailbone, leaving him in agony.

When North Korean guards discovered the blood-soaked sailor, they threw him onto the dining table, wrapped him in the plastic table cover, and dragged him down passageways and across the gangplank onto the dock at Wonsan. Woelk believed they were about to throw him into the harbor.

At the “Barn,” (prison) as the sailors called their first prison, he was placed in a cell with two other wounded men. For two days they received no food or medical treatment. Woelk slipped in and out of consciousness, moaning for help. The only uninjured man, Dale Rigby, did what he could with no supplies—begging guards for an empty bottle so Woelk could urinate and trying to comfort his shipmates as best he could.

Soon, Woelk became glued to the table cover by his own dried blood and could barely move. The guards entered holding bandannas over their noses to block the stench of infection. After about ten days, North Korean medics transferred him to another room, strapped him to a metal table, and—without anesthesia—began cutting into his flesh with scissors. When they were done, they had removed his remaining testicle and crudely stitched the wounds with what appeared to be kite string. Woelk’s screams echoed through the Barn, and other prisoners assumed they were hearing a brutal torture session.

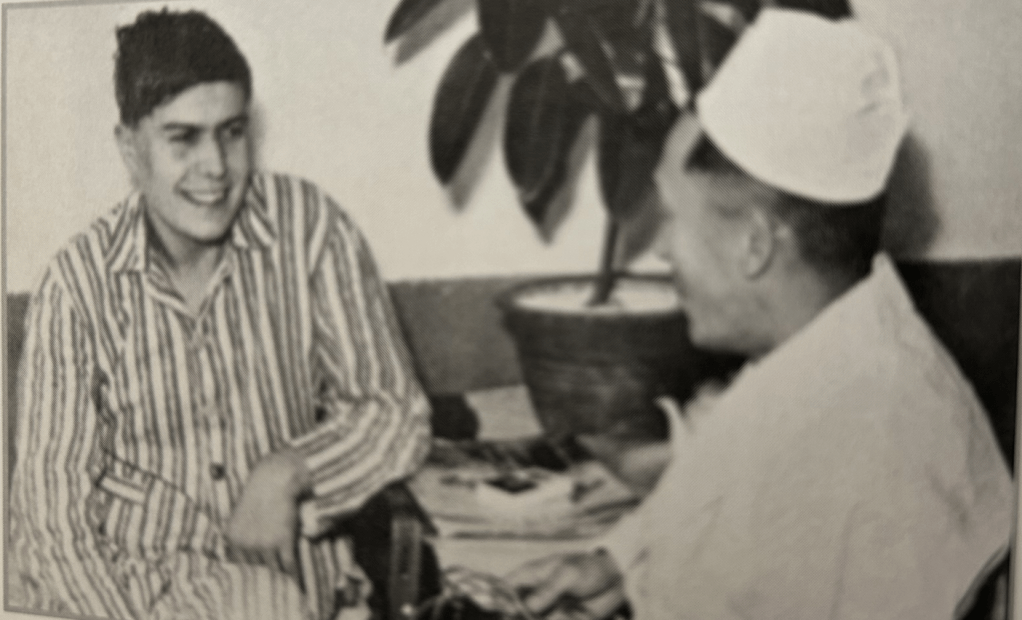

He was later moved to a hospital and left alone in a filthy room where paint peeled and bedbugs crawled over his sheets. Postoperative care consisted of a doctor jamming strips of gauze soaked in ointment into his wounds with forceps. He was not bathed or shaved, but as the days passed, his wounds slowly began to heal. The staff provided cigarettes, playing cards, and propaganda magazines, though none of them spoke English. Communist photographers frequently visited, even restaging his surgery for pictures. Woelk marked the days on the wall with a burnt match; one of those marks was for his twentieth birthday.

Eventually, he grew strong enough to stand. Seeing his reflection in a glass transom, he was stunned by his emaciated appearance—he had lost fifty-five pounds in less than two months.

Woelk’s almost miraculous return boosted morale, but it wasn’t the only cause for hope. Since their transfer to the “Country Club,” systematic beatings had largely ceased. Many of the officers from the Barn had followed them, but the guards were new. While they still occasionally slapped or struck the prisoners when unobserved, it seemed clear they had orders to ease up. The communists had already extracted much of what they wanted and now seemed to regard the sailors merely as pawns of the “warmongering Johnson clique in Washington.”

Life settled into a dull, predictable rhythm. Loud electric bells woke the men at six a.m., giving them only minutes to wash before morning calisthenics—weather permitting. They then polished their cell floors with rags and marched to breakfast: turnips, and whatever else the guards served.

Mornings were spent “reading” propaganda magazines, though most men simply dozed behind their open pages. After a one p.m. lunch—more turnips—they were allowed an hour for sports or exercise. Then came another period of mandatory study of communist “cultural materials,” followed by a six p.m. supper of, again, turnips. Lights-out came at ten, and baths were permitted twice a week.

“The typical day started in stupidity, proceeded through boredom, and ended in stupidity 16 hours later,” Schumacher later wrote in his memoir.

With discipline relaxed, Bucher reestablished his chain of command. Though forbidden to speak openly with his crew, he used fireman John Mitchell, assigned to clean his quarters, as his messenger. Through Mitchell, Bucher stayed informed—he knew who had been beaten, who had fallen ill, and who was nearing collapse. He offered whispered encouragement during exercise or mealtime, bolstering morale wherever he could.

Bucher urged the men to resist in small ways. When ordered to bow their heads like criminals, he mocked the gesture by bending deeply at the waist like a frail old man. When told to stop, he resumed walking upright—and was eventually allowed to continue that way.

He also encouraged laughter and defiance during Friday-night propaganda films. One film showed an American pilot deliberately bombing a little boy. As the narrator cried, “They have blinded the boy!” Bucher shouted back in the darkness, “Fuck you!”

The crew followed their captain’s lead, responding to orders with absurd exaggeration and irony. Their antics, reminiscent of Hogan’s Heroes, often left guards bewildered. When told to turn left, they turned right; ordered to halt, they walked straight into walls, piling up in comic disarray.

“Why you not march like soldiers?” a North Korean demanded in frustration.

“We’re American,” one sailor replied with deadpan humor. “We just don’t walk like you.”

Featured image:

A staged photograph showing FN Steve Woelk’s surgery

Source “Act of War”, by Jack Cheevers

10 December 2025 at 16:32

unforgiveable; these north koreans remain our enemies since the armistice only meant a break in the fighting while negotiations were supposed to continue. I still don’t understand why we extended friendship to the North Vietnamese led by John McCain, senator of Arizona, after the way our men were treated there. The least it could be as the Scots say, forgive your enemies but remember their names.

LikeLike