Key Points and Summary – The U.S. Navy’s ambitious Cruiser Modernization Program for its aging Ticonderoga-class ships was a high-profile failure.

-A damning GAO report revealed the Navy wasted $1.84 billion modernizing four cruisers that were ultimately divested before ever deploying.

-The program was plagued by soaring costs (over $500 million per ship), poor contractor performance, and the extreme technical difficulty of integrating modern systems onto 1980s-era hulls.

-The Navy ultimately concluded it was no longer cost-effective, canceling the program in favor of the new DDG(X) destroyer.

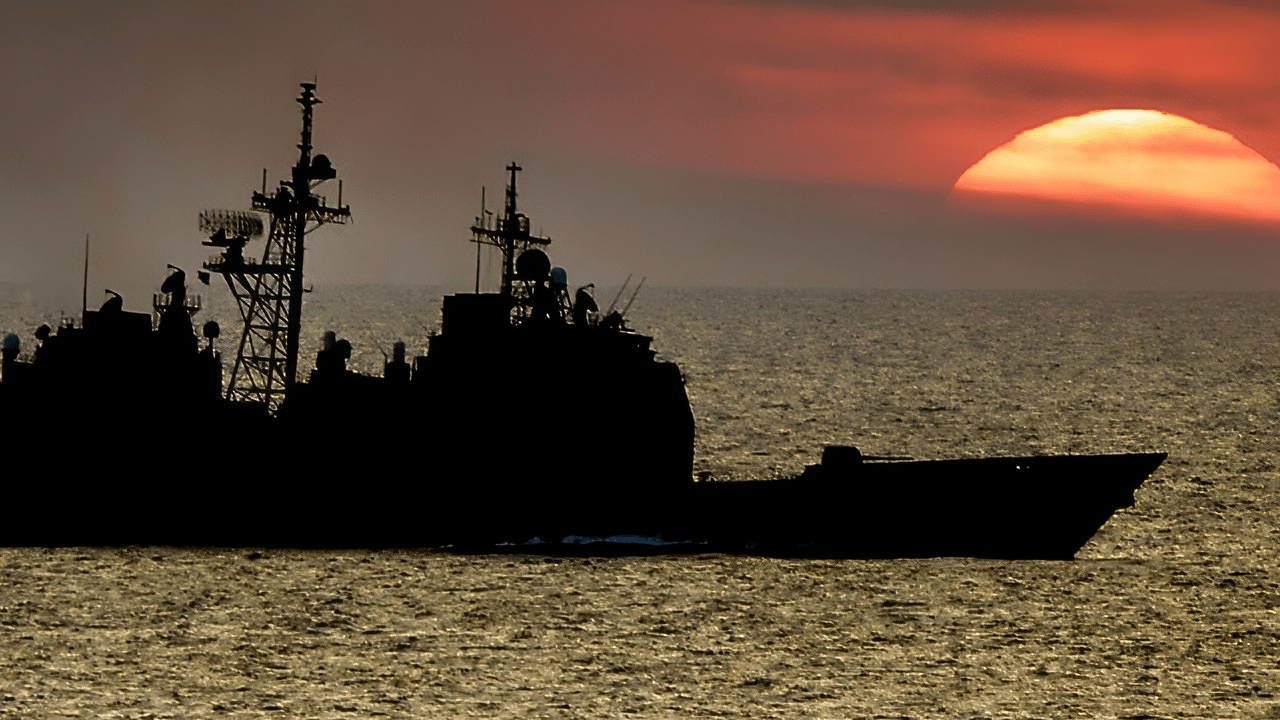

The U.S. Navy Wasted $1.84 Billion on a ‘Failed’ Ticonderoga-Class Ship Program

The U.S. Navy in the 2000s undertook a wide-ranging modernization program to extend the life of its Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruisers. The upgrade was extremely ambitious, but ultimately troubled.

Though many of the cruisers were commissioned at the height of the Cold War in the 1980s, the update program sought to keep the ships relevant well into the 2030s.

The program saw some success, but it bogged down in technical, budgetary, and managerial problems that led to years of delay, spiraling costs, and an extremely truncated collection of upgrades.

The Ticonderoga-Class Explained

The Ticonderoga-class cruisers were built for the U.S Navy from 1978 to 1994.

They were designed around the Aegis Combat System and its accompanying AN/SPY-1 radar. The cruisers’ potent air-defense capabilities protected the whole fleet, but by the 2000s, the cruisers were beginning to show their age.

Wear and tear on the hulls led to structural fatigue, and the class’ components, particularly the electronics and on-board computers crucial to Aegis operation, were losing their combat relevance.

The Navy had two choices: Retire the Ticonderoga-class outright, leaving a potential air-defense gap, or modernize them to extend their service life.

The Navy had previously attempted to field a replacement for the Ticonderoga-class, but after the CG(X) Next Generation Cruiser program was cancelled, the Navy decided to launch the Cruiser Modernization Program.

Its goals were ambitious: The program would comprehensively overhaul the Ticonderoga’s combat systems, radar, and hulls, and enable the vessels to operate alongside newer Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and other more advanced ships

The Government Accountability Office Findings

A report from the Government Accountability Office summarized the project’s implementation and evaluated its overall success.

The report’s conclusions were damning. “Since 2015, the Navy has spent about $3.7 billion modernizing seven of the Ticonderoga class guided-missile cruisers—large surface combatants that provide key air defense capabilities,” the GAO wrote.

“However, only three of the seven ships will complete modernization, and none will gain 5 years of service life, as intended.

The Navy wasted $1.84 billion modernizing four cruisers that have now been divested prior to deploying. The Navy also experienced contractor performance and quality issues across the cruiser effort.

For example, the contractor performed poor quality work on USS Vicksburg’s sonar dome—a critical element of the Anti-Submarine Warfare mission area—resulting in additional cost and schedule delays due to necessary rework.”

One of the core issues with the modernization program was the Ticonderoga’s complexity.

Many of the ship’s systems were built according to 1980s-era architecture, and integrating updated radar systems onto older ships proved more complicated than the Navy originally anticipated.

Structural modifications needed to accommodate new systems on the ships led to complex standardization procedures.

Initial cost estimates for updating the cruisers came to about $200 million per ship.

But by the 2010s, refit costs for some ships totaled more than $500 million, and the complexity of the work pushed back schedules.

The shipyards responsible for the upgrades also experienced long idle periods, which affected the construction of other ships and submarines for the U.S. Navy — a potent ripple effect on production.

Naval and congressional priorities also changed over the course of the program. The Budget Control Act of 2011 imposed spending constraints and disrupted the Ticonderogas’ modernization. Most significantly, as time went along, there were diminishing returns on investment into the Ticonderoga modernization program.

It became clear that it would cost the Navy the same—or in some instances more—to modernize a cruiser than to build a new Flight III Arleigh Burke-class destroyer. Furthermore, a modernized destroyer was not a new build; it would only see an additional 10 to 15 years of service, compared to much longer service timelines for new-build ships.

A Story of Navy Failure

The Ticonderoga-class modernization was a failure—and a significant, high-profile failure at that. Though there are many reasons why the Navy program was unsuccessful, one of the core issues was a mismatch between 21st-century technological systems and 20th-century ship infrastructure.

Inconsistent objectives, a shaky budgetary situation, and, in some cases, poor construction and implementation only made matters worse.

The U.S. Navy finally decided that modernizing the Ticonderoga-class would no longer be cost-effective, and in fact it might not be achievable at all. The service opted instead to invest in the DDG(X) guided-missile destroyer program.

About the Author: Caleb Larson

Caleb Larson is an American multiformat journalist based in Berlin, Germany. His work covers the intersection of conflict and society, focusing on American foreign policy and European security. He has reported from Germany, Russia, and the United States. Most recently, he covered the war in Ukraine, reporting extensively on the war’s shifting battle lines from Donbas and writing on the war’s civilian and humanitarian toll. Previously, he worked as a Defense Reporter for POLITICO Europe. You can follow his latest work on X.

Source: nationalsecurityjournal.org

Leave a comment