Operation Desecrate One was a World War II United States Navy operation on 30–31 March 1944. Desecrate One was part of the preparations for Operations Reckless and Persecution, the Allied invasion of western New Guinea.

Desecrate One involved attacks by the aircraft carriers USS Enterprise (CV-6), USS Bunker Hill (CV-17), USS Hornet (CV-12), USS Yorktown (CV-10), USS Lexington (CV-16), USS Monterey (CVL-26), USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24), USS Cowpens (CVL-25), USS Cabot (CVL-28), USS Princeton (CVL-23), and USS Langley (CVL-27) against Japanese military bases on and around Palau. Thirty-six Japanese ships were sunk or damaged in the attacks. Among these ships were significant auxiliary vessels such as the torpedo boat tender Kamikaze Maru, submarine tender Urakami Maru, aircraft transport Goshu Maru, repair ship Akashi and the tankers Iro, Ose, and Sata. In addition, TBF and TBM Avengers from the carriers laid extensive fields of mines in and around the channels and approaches to the Palau Islands in the first tactical use during the Pacific War of mines laid by carrier aircraft.

OPERATION “DESECRATE ONE”

Strikes and Sweeps on PALAU

King Day – 30 March

Japanese Language Officers:

COMCENTPACFOR – Lt. Comdr. G. M. Slonim

(in USS NEW JERSEY)

CONITASKFOR 58 – Lt. (jg) C. A. Sims

(in USS LEXINGTON)

COMTASKGRP 58.2. – Lt. (jg) W. W. Burd

(in USS BUNKER BILL)

COMTASKGRP 58.3 – Lt. (jg) E. B. Beath

(in USS YORKTOWN)

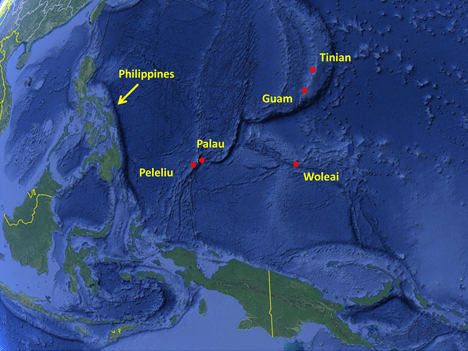

The mission of Operation “DESECRATE 1” was to attack and destroy enemy aircraft and installations at PELELIU Air Base and WOLEAI (MEREYON Air Base) and attack and destroy enemy shipping in PALAU Harbor.

On 28 March, Japanese search planes from WOLEAI were active in the general area of the U. S. force, and although there was nothing to indicate contact with the main body of the U. S. striking force, a contact grid at 1005 in the morning was within 60 miles of the main body, and a report by another Japanese plane of contact with U. S. carrier planes indicated the presence and general location of the U. S. carrier force in the area was ‘clown. However, no attacks were experienced that day or the following night, although RI was certain the presence of the U. S. Fleet was no longer a secret.

29 March found Japanese aviation active with the obvious intent of seeking out and destroying the marauding Blue striking force. Search planes from both WOLEAI and PALAU made definite contact with the striking force in the morning. After the initial contact at 1045 by PELELIU-based planes, the Japanese dispatched at least three shadowing craft from that base and maintained contact with the Blue force through the day. At 1655, four new plane groups appeared on the PALAU circuit. Thereafter, tactical activity increased, culminating in a well-coordinated dusk torpedo attack. After completion of the attack, the surviving planes requested homing bearings and returned to PELELIU. However, when DAVAO Air Base suddenly appeared on the circuit and thereafter assumed control of the flights, it appeared that the surviving aircraft had merely refueled at PELELIU and further withdrawn to DAVAO to avoid the next day’s carrier strikes.

Collateral information indicated the Japanese planned a predawn attack for the morning of 30 March, but the attacks failed to materialize. Many planes appeared airborne on air circuits, but the Blue CAP destroyed one group of enemy planes before it reached the force, and drove off-or shot down snoopers arriving alone or in pairs. Eventually great confusion arose among the airborne Jap planes, some asking for bearings, some asking in plain language “Shall we return?” and others inquiring of the base if they were under air attack or if landings there were unsafe. Disconcertion among the air-borne Jap planes seemed to result from a high precedence dispatch originated by WOLEAI at 0815 and subsequently delivered to all planes. The U. S. striking force launched planes against PALAU, arriving over the target at 0600, at which time PELELIU Air Base sent a full air raid alert report. However, despite the failure of their–dawn attack against the Blue Fleet, the Japanese succeeded in maintaining contact throughout the day, and-the appearance of GUAM and TINIAN on the air circuits, working both planes and PELELIU, gave rise to suspicion of a dusk attack from the MARIANAS to land after the attack at PELELIU. At 1704, a plane group leader advised a shadowing guide plane that he would arrive at the target at 1845, thereby giving the U. S. Fleet Commanders nearly two hours to prepare for the attack. At 1815, the same grow: commander requested the same guide plane to drop flares, which was done, and the guide plane, at 1836, advised the group commander the drop had been completed. At 1833, the attack group commander gave the order for the first group to attack and ordered the second group to attack at 1854. Surviving attack planes after completion of the attack requested bearings for return flight to PELELIU.

31 March found the planes from the U. S. carrier force alerting PALAU against an attack at 0629. By 0800, eight TITIAN search planes were up, which by signal strength seemed to be searching south toward PALAU. At 0815, two search planes were up working PALAU. At 1017, a TINIAN-based Japanese plane contacted the U. S. force, and the rest of the day the air circuits were active with sporadic snooping and attack efforts by the Japanese. No coordinated attack developed, however, probably because Blue CAP made it impossible for the tracking planes to maintain contact in spite of vigorous efforts to do so.

On 1 April, the target of the U. S. striking force was shifted from PALAU to WOLEAI. Tracking activity by Orange planes based on TINIAN continued all the night of 31 March – 1 April. Night fighters from the U. S. carrier force were despatched to heckle WOLEAI, which reported enemy planes overhead at 0133. This prevented the Japanese from staging an attack through that base. The first strike from the carriers was reported by WOLEAI at 0553. Search activity from GUAM and PALAU by the Japanese apparently lost contact during the early morning, and failed to locate the Blue striking force the rest of the day. The U. S. force retired after the WOLEAI strike without incident.

“DESECRATE 1” provided ship-borne RI [Radio Intelligence] an opportunity to study and exploit to the fullest our knowledge of Japanese air tactics. The development of attacks was clearly defined, subsequent to initial contact by Japanese search planes with the U. S. striking force. Normally, a #1 message sent blind by the controlling base (GUAM, PELELIU or WOLEAI) to those collective Charlie calls was an indication that an attack group was airborne. The three collective calls would presumably be identified as contact, guide (illumination) and attack groups. A P.O.W., picked up during the operation, stated the senior pilot of an attack mission is in the attack group and coordinates the attack.

Source: Command Display, Corry Station, Pensacola, FL.

30 March 2025 at 13:52

Strongly recommend visiting the Corry Command Display. It had been on my bucket list for years and finally checked it off in October 2024. Only spent one day touring the display, but was considering extending my stay to visit longer. I’m so thankful volunteers stepped up to help man the display so it can continue to provide incredible memories like those detailed in todays article.

CTRC-CDR 65-95

LikeLike