What no one in the cryptographic community realized at the time was that a U.S. Navy radio specialist, John Anthony Walker Jr., had recently begun selling classified codes to the Soviet Union. In late 1967, Walker walked into the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., offering to sell a wide range of top-secret documents related to Navy operations. The Soviets accepted without hesitation. In early January 1968, just before the USS Pueblo was seized, Walker left a package of KW-7 encryption codes at a dead drop in the Virginia countryside.

Walker would go on to assemble one of the most damaging spy rings in American history. He recruited his son, a communications technician aboard an aircraft carrier; his brother, a retired Navy officer; and his best friend, a Navy radioman, to help him steal highly sensitive military material.

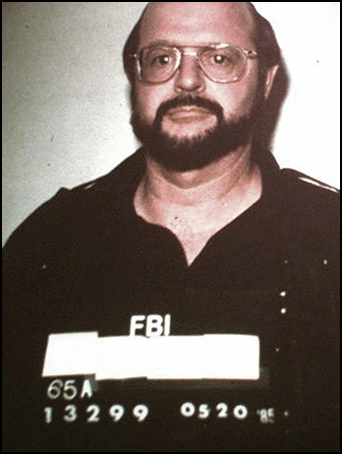

The ring operated undetected for an extraordinary 17 years until Walker’s ex-wife alerted the FBI, leading to his arrest in 1985. The damage he inflicted on national security was “incalculable,” according to FBI agent Robert Hunter, who helped capture him. Through Walker’s treachery, the Soviets learned U.S. carrier tactics, how to sabotage spy satellites, the locations of underwater listening devices used to track Soviet submarines, and details on troop movements in South Vietnam. Even more shocking, at the time of his arrest, Walker was attempting to hand over authentication codes that could have been used to launch U.S. nuclear missiles.

Because so many American military units relied on the KW-7 encryption machine, the NSA decided not to replace it after the Pueblo seizure. Instead, it issued a modified version, assuming daily code changes would keep it secure. When the NSA distributed new technical manuals describing the updates, Walker promptly sold a copy to the Soviets.

Walker’s most effective partner was Jerry Whitworth, a mild-mannered chief warrant officer who fell completely under Walker’s sway. Whitworth photographed technical manuals for the KW-7 and KWR-37 systems, as well as code lists and publications for five other cryptographic systems. Together, they provided the Soviets with the blueprints to nearly every major U.S. code device. “For more than 17 years, Walker enabled your enemies to read your most sensitive military secrets. We knew everything!” boasted Boris Solomatin, the KGB’s station chief in Washington.

Cunning and manipulative, Walker also recruited his son Michael and his older brother Arthur. He even tried, unsuccessfully, to recruit his daughter, who was serving in the Army Signal Corps. Over the years, he met KGB handlers nearly a dozen times in Vienna, Austria, delivering rolls of microfilm. On one occasion, he brought his mother along, convincing her to wear a money belt containing $24,000 in KGB payments — completely unaware she was smuggling Soviet cash through U.S. Customs.

From his posts aboard nuclear submarines and later at Atlantic Fleet headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia, Walker stole vast quantities of classified material. “A Kmart store has better security than the U.S. Navy,” he later bragged. When faced with an FBI background check, he forged his own clearance to prevent agents from interviewing his estranged, hard-drinking wife, Barbara — the one person who knew how he was earning an extra $4,000 a month beyond his Navy salary. He even urged the KGB to “eliminate” her. The Soviets code-named him “Agent No. 1” and made him an honorary admiral.

After his arrest, KGB defector Vitaly Yurchenko revealed that, thanks to Walker, the Soviets had deciphered over one million U.S. military messages. The information flow was so massive that the KGB built an entire facility in Moscow to analyze it. “It was the greatest case in KGB history,” Yurchenko declared. “If there had been a war, we would have won it.”

Though Walker denied that his espionage directly contributed to the Pueblo incident, the full extent of his role remains uncertain. Even decades later, it’s unclear whether the Soviets combined Walker’s stolen data with what they obtained from the captured ship. Yet it may not matter — because Walker’s spy ring alone provided both the codes and the technical blueprints that allowed Moscow to penetrate America’s most sophisticated encryption systems.

Source “Act of War”, by Jack Cheevers

22 December 2025 at 09:15

Despicable! I pray his life sentence here on earth that ended in 2014 will continue for enternity with the devil to whom he sold his soul.

LikeLike

22 December 2025 at 13:36

That any of the members of the Walker Spy Ring are still alive is an insult to the memory of those who have died defending our nation! Hang ‘em, shoot ‘em then electrocute ‘em!

LikeLike