In San Diego, two black dots appeared on the horizon, getting bigger by the moment. “They’re coming in!” someone shouted. The C-141 Starlifters circled the airfield and seemed to land in slow motion. The big jets taxied toward the waiting families and cut their engines. A tense stillness settled over the crowd as uniformed sailors unrolled red carpets up to the aircraft. Then a hatch on the lead plane popped open, and Pet Pucher wobbled down the staircase, worn-looking but smiling.

To his amazement a Navy band was playing “The Lonely Bull.”

“It’s so great!” he exulted. “You’ll never know how great it is!”

A moment later he and Rose were locked in a fierce embrace, their tear-streaked faces crushed together.

“I love you, Rose,” the skipper said simply.

His men ran into the hungry arms of their loved ones. “Oh, Anthony! Oh, darling, I’m so happy!” cried a gray-haired mother as she embraced her son. An older man in a checked vest pumped away at his boy’s hand, saying, “Well Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas. By golly, it’s good to see you.” One wife supported a pale, gaunt husband who seemed too weak to stand on his own; another pressed her head hard into her man’s chest, drawing comfort and strength from his presence. A sailor held his infant son for the first time, regarding him with pride and wonder.

“These were the nation’s Christmas present,” a local newsman summed up, “and the emotion was almost too big to handle.”

Like two small islands of grief amid this ocean of joy stood Duane Hodges’s parents. Jesse and Stella Hodges were plain, deeply religious people from Oregon with faces out of a Dorothea Lange photograph. The Navy had never officially explained how their son died, and so they came to San Diego seeking the truth from his shipmates. Rose brought the bereaved couple over to meet her husband and placed a steadying hand on his back as he struggled to get out some words of comfort.

“Mr. Hodges, I – I can’t tell you what a tremendous job your son did for us,” CDR Bucher said, looking intently into the retired millworker’s tear-dappled face. “I’m so, so sorry that he couldn’t return alive with us.”

“Captain, I’m so glad you got back,” replied Hodges, gripping Bucher’s hand.

The stricken skipper wrapped his arms around both parents and told of the North Korean shell that hit their son and his death in a shipmate’s arms. “What were his last words?” Mrs. Hodges asked. Bucher said he wasn’t there at the time and didn’t know. But he promised to put her in contact with the sailor who’d cradled her boy in his final moments.

Bucher was led to the speaker’s podium, flanked by military and political dignitaries. Governor Reagan spoke to him briefly, recalling the captain’s role as an extra in Reagan’s 1957 movie Hellcats of the Navy, filmed in part aboard one of Bucher’s old submarines, the Besugo. The captain congratulated him on his excellent memory and turned to face a brace of microphones. TV lenses zeroed in on his tired face.

He spoke of his obsessive worrying in prison about “the embarrassment that we caused the United States by losing one of its very fine ships to the North Koreans.” He recalled the Pueblo getting shot up at “point-blank range.” When he mentioned Duane Hodges’s mortal wounding, he choked up. His jaws moved but no sound came out. An admiral patted his shoulder.

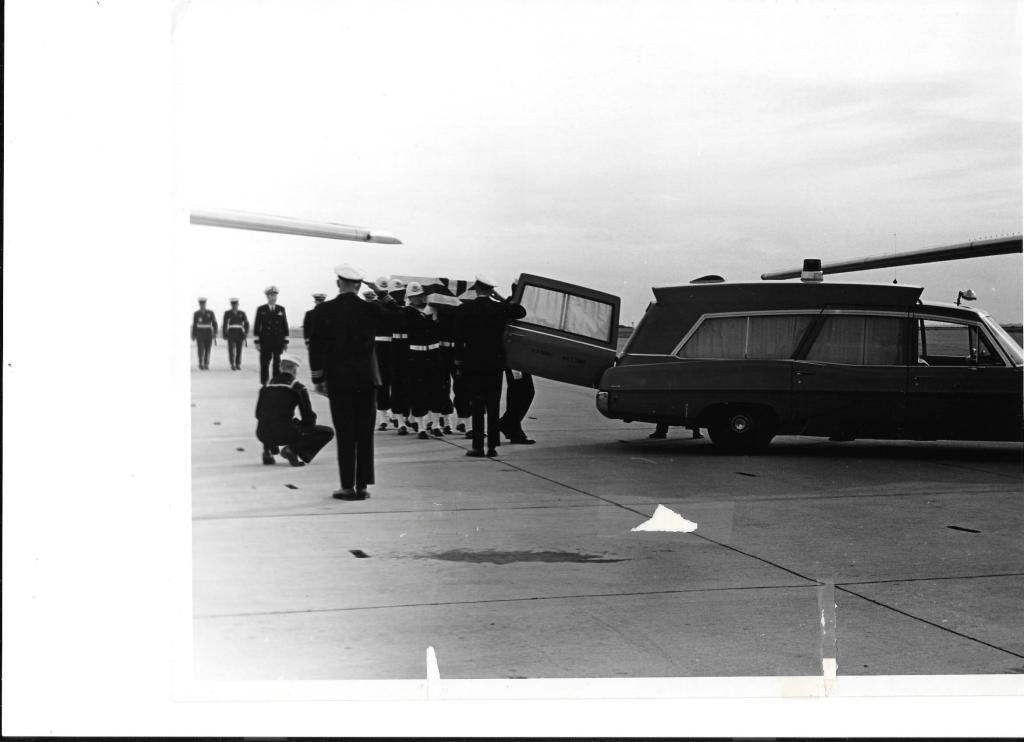

Moments later, six Navy pallbearers in dress blues and white helmets carried Hodges’s flag-draped coffin from a Starlifter to a gray hearse. An honor guard snapped off crisp rifle volleys at the winter sky. As muted trumpets played taps, Bucher and his men came to attention and saluted their fallen comrade. Reagan made some welcoming remarks, as did the mayor of San Diego, who also offered Bucher a key to the city. But the jittery politician kept extending and withdrawing the key, doing so three or four times. Finally he finished his speech, dropped the key in his pocket, and walked away. Bucher had his first really good laugh since leaving North Korea.

The crewmen and their families climbed into eight buses for the short ride to the U.S. Naval Hospital at Balboa Park, in the gentle hills overlooking downtown San Diego. Rolling through the base gates, the sailors met a completely unexpected sight: multitudes of cheering San Diegans lining the route to the hospital, standing three and four deep in places. The civilians pounded car horns, whistled, flashed thumbs-up, and shook handmade “welcome home” signs.

Bucher grinned and waved at the crowds like a barnstorming senator. The wild outpouring of public joy, however, unnerved some of the others.

Gazing out a window, LTJG Schumacher wondered for the thousandth time whether he could’ve done more to resist the North Koreans. LT Steve Harris’s mother, Eleanor, an effervescent Boston-area schoolteacher, noticed that most of the wan-looking sailors on her bus weren’t waving back.

“Wave to them!” she urged. “You should all wave to them!”

Her son tried to restrain her. “Mother, we’re not heroes,” he said mildly. “We’re just a bunch of ordinary guys who were in the right place at the wrong time.”

The buses passed a little boy, clad only in faded brown shorts, jumping up and down as he waved a small American flag. For many passengers the sight of the dirt-streaked kid and his guileless patriotism was too much. “Slow tears came upon faces all along the aisle, parents and sons alike,” Eleanor Harris wrote later. “An older sailor across from me—at least his hair was gray—was crying into thin, gnarled hands.”

The convoy arrived at the hospital. With 2,600 beds and more than 300 doctors, the Balboa complex was the largest military medical facility in the world. The sailors lugged their white ditty bags into a four-story pink stucco building normally inhabited by Navy hospital corps students. Dubbed the “Pink Palace,” it was to be their home for the next few weeks. Murphy was impressed by the luxuriousness of the two-man suites: carpeting, writing desks, and beds long enough to accommodate American frames. The only drawback was that he had to share his digs with Bucher.

By now the captain was bleary with fatigue. His head was ready to burst from the day’s excitement and stress. Fewer than 55 hours had passed since he crossed the Bridge of No Return. He limped over to the adjacent enlisted men’s club to have dinner with his sailors, only to be mobbed by their exuberant, grateful families. “Some of the handshakes I received from the fathers and brothers of my crew nearly broke my hand,” he was to write of the experience. “Mothers and wives hugged and kissed me. It was overwhelming.” After dinner he and Rose sneaked to the back of the room for a semiprivate reunion with kisses, hand-holding, and tender words.

The Navy was working hard to satisfy the needs of the crewmen and their kin. It had paid for last-minute plane tickets to San Diego for scores of family members. Phones were set up so sailors could make free calls to friends and relatives all over the country. “An admiral just fetched me a cup of coffee,” a bemused enlisted man told LT Murphy. By the same token, the crewmen were confined to the hospital grounds for at least the next several days. They had orders not to talk to the media, not even about the weather. The Navy wanted to be sure no military secrets leaked, and no one said anything that might later jeopardize himself legally. Armed sentries were posted to keep news reporters away from the Pink Palace.

On Christmas morning, the crew went on a shopping spree at the Balboa Post Exchange. With $200,000 in back pay in their collective pockets, they snapped up cameras, watches, appliances, coats for their wives, and toys for their kids. Bucher moved easily among his men, joking and wishing them a merry Christmas. That evening, under the Navy’s liberal definition of “next of kin,” more than 500 people jammed the dining room, feasting on turkey, rainbow trout, beef prime rib, French onion soup, and tomato bisque. Catholic and Protestant services were held before an altar jury-rigged out of a table, a sheet, and two candles; the faithful took communion in the soft, flickering light.

“When we sang ‘Joy to the World,’” one mother said, “you never heard anything like it.”

The happy homecoming triggered a widespread catharsis. “Never, in 35 years, have I been so bustlingly proud to be an American,” a San Diego man wrote to a local newspaper. “Standing on 10th Avenue, with many others, to welcome home the Pueblo crew was an overwhelming experience.” America’s first television-age hostage crisis—a phenomenon that would become distressingly familiar in the future—had ended remarkably well. The survivors were safe, they were in one piece, and—thanks to the Johnson administration’s dogged diplomacy—they were back home with loved ones just in time for Christmas.

Lyndon B. Johnson was widely praised for not succumbing to the temptation to unsheathe military force during the long standoff with Pyongyang. The New York Times hailed his “wise decision … to accept some sacrifice of American pride.” Even some hawks applauded the gentler approach. “Many of our members called for speedier and forceful action immediately after the Pueblo was illegally seized,” the national commander of Veterans of Foreign Wars wrote to the White House. “Many more became most impatient as the months dragged by. In retrospect, however, the Nation’s restraint and patience have paid off.”

Source “Act of War”, by Jack Cheevers

20 December 2025 at 10:54

I was at Camp Kaiser Korea, in my mess hall when they were released, we all stood & cheered

LikeLike

20 December 2025 at 19:46

For those of us that understand and took the oath, the surrender was an act of cowardice.

LikeLike