The Pueblo crisis left the United States with only one viable channel to communicate with North Korea: the Military Armistice Commission at Panmunjom. It was a setting already steeped in history—the same site where the Korean War armistice had been signed in 1953—and it would again become the stage for one of the most delicate negotiations of the Cold War.

The talks opened in February 1968, led by two principal negotiators:

- Major General Gilbert H. Woodward, U.S. Army, representing the United Nations Command, and

- Major General Pak Chung-kuk, Korean People’s Army, representing North Korea.

From the beginning, the North Koreans set forth three uncompromising conditions for the release of the USS Pueblo crew:

- The United States must admit that the Pueblo had intruded into North Korean waters.

- The United States must apologize for the intrusion.

- The United States must assure that such an incident would never happen again.

To Washington, these demands were unacceptable. Any admission of guilt would contradict both the Navy’s navigational data and established international maritime law. The negotiations quickly bogged down, marked by inflexible rhetoric, propaganda-laden statements, and long periods of silence between sessions. Yet despite the stalemate, both sides sought a resolution that would end the crisis without public humiliation.

A Creative Proposal from Bethesda

Amid the frustration in Washington, an unexpected voice offered a creative way forward. Eleanor Leonard, wife of Rear Admiral John Victor Leonard—who was monitoring the negotiations from the Pentagon—suggested a diplomatic maneuver from her home in Bethesda, Maryland.

Drawing on an informal concept circulating among diplomats known as the “helicopter scenario,” she proposed a symbolic act that could meet North Korea’s demand for an apology without conceding guilt. Eleanor refined the idea even further: the United States should publicly repudiate any apology before signing it.

This “pre-repudiation,” she reasoned, would render the statement meaningless as an admission of wrongdoing while still allowing North Korea to claim victory for domestic consumption. Her concept resonated with officials who recognized that a face-saving compromise might be the only way to free the crew without violating U.S. principles or legal standing.

The “Pre-Repudiated” Apology

After months of diplomatic frustration, Eleanor Leonard’s idea took shape in what became known as the “pre-repudiated apology.”

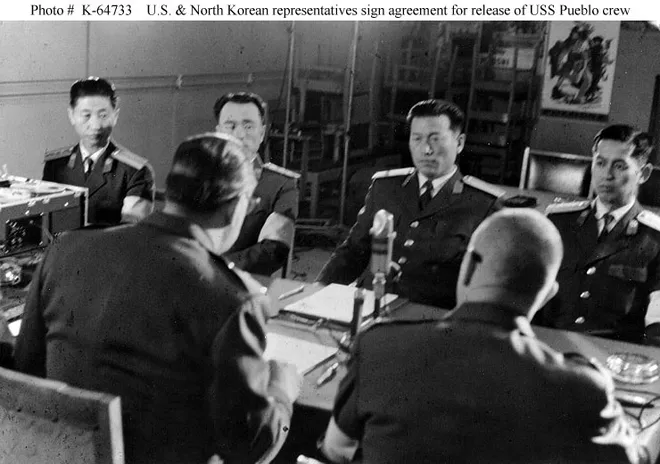

At the 28th negotiating session on December 23, 1968, General Woodward presented a document that, on its surface, met North Korea’s three conditions: an admission, an apology, and a pledge to prevent future violations. As General Pak Chung-kuk looked on, Woodward read the document aloud and prepared to sign it—but not before issuing a crucial statement for the record.

Woodward declared that the United States did not admit any of the charges and was signing the document solely to secure the release of the crew. In that single act, the United States formally disavowed the document’s contents even as it was being signed.

The maneuver allowed both sides to achieve their objectives:

- North Korea obtained a signed document it could publicly present as an American confession of guilt.

- The United States preserved its integrity by clearly and publicly repudiating the apology before and after the signing.

Moments after the signing, General Pak accepted the document, and the release process began. On the same day—335 days after their capture—Commander Lloyd M. Bucher led his 82 surviving crewmen across the Bridge of No Return into South Korea. The 83rd crew member, Fireman Duane Hodges, had been killed during the initial North Korean attack on the Pueblo.

Aftermath and Legacy

Upon the crew’s return, the U.S. government immediately emphasized that it had not apologized and did not acknowledge any wrongdoing. Officials described the signed document as a “formality under duress.” North Korea, by contrast, celebrated the text as proof of American capitulation, broadcasting it widely as a symbol of the regime’s strength.

Despite its awkwardness, the “pre-repudiated apology” has endured in diplomatic history as a remarkable, if morally ambiguous, example of Cold War negotiation. It was an ingenious balancing act—an effort to reconcile humanitarian necessity with political and legal principle.

For the Pueblo crew, the exchange marked the end of nearly a year of brutal captivity. For historians, it remains a study in the limits of diplomacy under coercion and a testament to the creative lengths nations may go to resolve crises without bloodshed. It also stands as a vivid reminder that in international diplomacy, words—carefully chosen, strategically delivered—can be as powerful as any weapon.

Featured image:

Repatriation of USS Pueblo Crew, December 1968 Representatives of the United States and North Korean governments meet at Panmunjom, Korea, to sign the agreement for the release of Pueblo’s crew, 22 December 1968. Major General Gilbert H. Woodward, U.S. Army, Senior Member, United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission, is in the left foreground, with his back to the camera and Major General Pak Chung-kuk, Korean People’s Army, representing North Korea sitting directly in front of Woodward.

Reference:

U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXIX: Korea.

Leave a comment