When Commander Bucher tried to learn what had become of Glorious General (G.G.), he discovered that the prison commandant had once again disappeared. When G.G. finally returned a few weeks later, the warmth and arrogance he had once displayed were gone—replaced by a cold, contemptuous hostility toward the Americans.

G.G. wasted no time revoking every privilege the crew had earned. There would be no more Ping-Pong or card games. The watery turnip soup once again became their primary meal. Guards multiplied from two to twelve on each floor, and the sailors were once again forced to bow their heads in submission whenever a captor appeared.

Other ominous signs followed. The Bear, one of the guards, had been absent for some time but now returned more violent than ever. One day, without warning, he dragged a sailor from his room and hurled him against a wall. Quartermaster First Class Law and two of his cellmates were brutally beaten. Overseeing this growing cruelty was a squat, shaved-headed North Korean colonel responsible for daily discipline. The crew called him “Odd Job,” after the menacing, bowler-throwing villain from the James Bond films. He strutted through the halls with a smug grin, clearly aware of the fear he inspired.

As the abuse intensified, so did talk of escape. By mid-November 1968, snow was falling again, and many crewmen doubted they could endure another brutal winter in the “Country Club.” Seaman Ramon Rosales lay motionless on his bed, crippled by fever. When Bucher demanded medical help for him, G.G. merely laughed.

With escape discussions underway, the need to complete the secret radio became urgent. No one wanted to risk an escape attempt if peace talks at Panmunjom were close to success. The only way to know was to pick up U.S. Armed Forces Radio or a South Korean news station. Communication Technician Third Class Strano had nearly finished assembling a crude crystal set. He managed to create a working battery and even discovered an antenna fastened to the wall outside his cell window. The last missing piece was an earphone, and Radioman Second Class Hayes believed he could fashion one from parts scavenged from the prison’s movie projector.

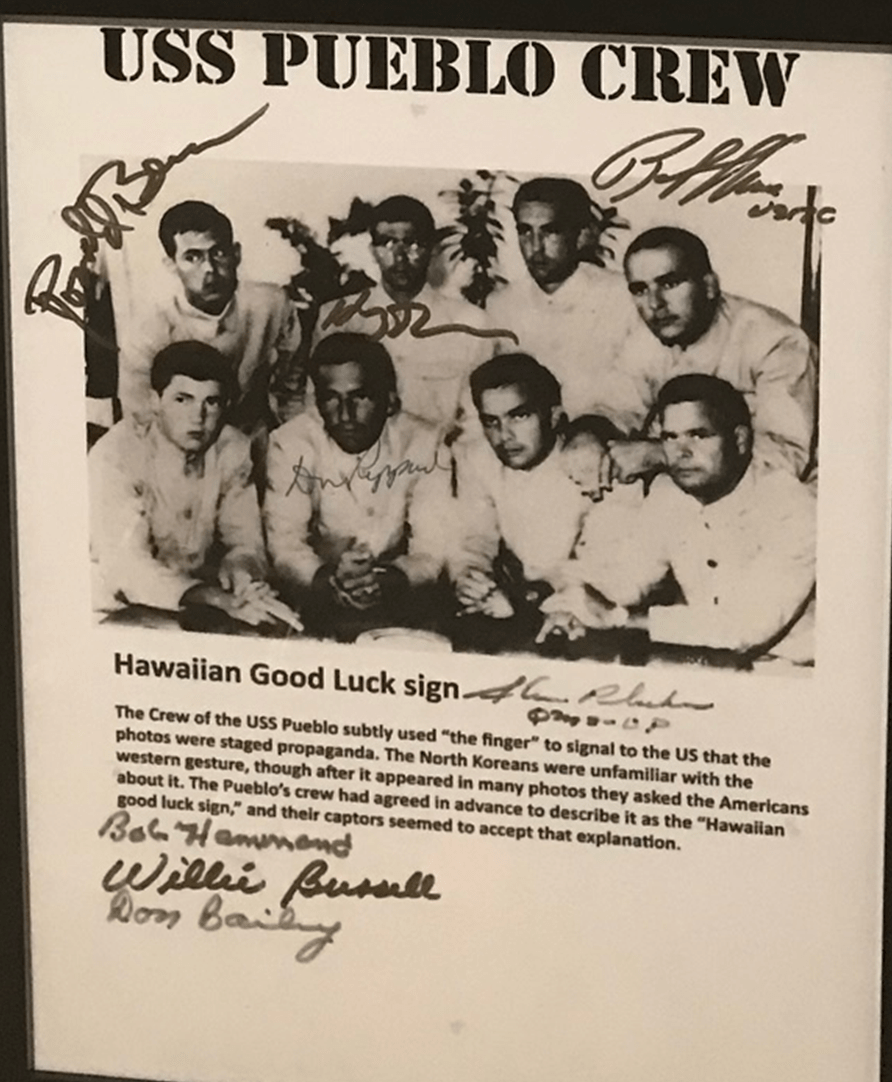

Then, one evening, G.G. summoned the Pueblo’s officers. He appeared enraged, shaking with fury. “Do you play us for the fool?” he shouted. On the table before him lay a copy of the Far East edition of Time magazine. It was opened to a photograph of eight grim-faced crewmen from QM1 Law’s cell—three of them defiantly raising their middle fingers. In tense silence, Bucher and his officers read the caption:

“The North Koreans are having a hard time proving to the world that the captive crewmen of the USS Pueblo are a contrite and cooperative lot. Last week Pyongyang’s flacks tried again – and lost to the U.S. Navy. In this class-reunion picture, three of the crewmen have managed to use the medium for a message, furtively getting off the U.S. hand signal of obscene derisiveness and contempt.”

Ironically, the photograph reached Time because of QM1 Law himself. He had mailed a copy to his uncle in Tacoma, who passed it to a local newspaper. From there, the image was picked up by the Associated Press and circulated across the United States. Not everyone understood its meaning—The Detroit News, consulting deaf press operators fluent in sign language, reported that the sailors were signaling the word “help.” But The New York Times and The Washington Post published the picture prominently, letting the gesture speak for itself. Time went further, explicitly explaining the meaning of the salute—and in doing so, sealed the crew’s fate.

LT Murphy stared at the magazine in shock, realizing the North Koreans had been humiliated before the entire world. He imagined the Soviets and Chinese laughing behind closed doors at their bumbling ally’s expense. The North Koreans knew they had been deceived. They began combing through every film and photograph of the Pueblo crew, searching for other signs of hidden defiance. Bucher felt an immense surge of pride in his men—they had found a way to tell the world they would never submit to communist coercion.

But he also knew the truth of what would follow; they were about to pay dearly for their defiance!

Source “Act of War”, by Jack Cheevers

Leave a comment