Christian Andreas Doppler was an Austrian physicist and mathematician whose 1842 description of what we now call the Doppler Effect fundamentally changed the understanding of wave phenomena. His insight—that the observed frequency of a wave depends on the relative motion between the source and the observer—forms a cornerstone of modern physics, astronomy, and engineering.

Early Life and Education

Doppler was born on November 29, 1803, in Salzburg, Austria, into a family of stonemasons. Frail health prevented him from entering the family trade, and he instead pursued studies in mathematics and physics.

He attended the Polytechnic Institute in Vienna (now TU Wien), where he was influenced by prominent mathematicians and scientists of the early 19th century. After graduation, Doppler worked as an assistant to Adam Burg, a professor of mathematics, and later began a career in academia.

Academic Career and Research

In the 1830s, Doppler held several teaching positions in Prague. By 1835, he was a professor of mathematics and geometry at the State Secondary School in Prague, and later at the Prague Polytechnic Institute.

His early research covered geometry, light, and sound, but he became particularly interested in how motion affects the perception of waves. This interest led to his most famous work, which he presented in 1842.

The 1842 Paper: Birth of the Doppler Effect

In his paper, “Über das farbige Licht der Doppelsterne und einiger anderer Gestirne des Himmels” (“On the Coloured Light of the Double Stars and Certain Other Stars of the Heavens”), Doppler proposed that the color (frequency) of starlight changes depending on whether the star is moving toward or away from an observer on Earth.

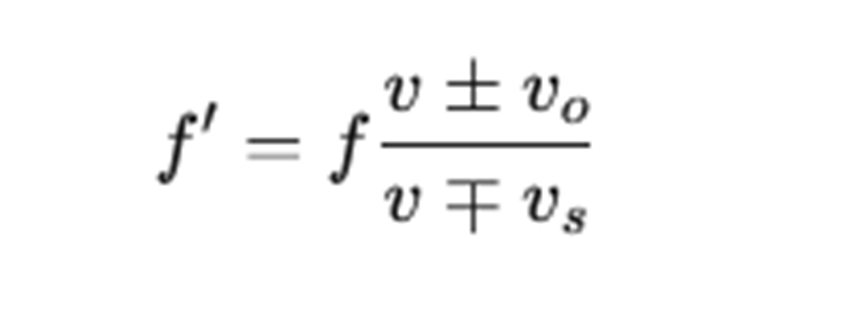

In modern terms, he was describing a frequency shift due to relative motion between the source and observer—what we now express mathematically as:

where:

f′ = observed frequency

f = source frequency

v = velocity of the wave in the medium (e.g., speed of sound in air or light in vacuum)

vo = velocity of the observer (positive if moving toward the source)

vs = velocity of the source (positive if moving away from the observer)

The plus/minus signs depend on whether the source or observer is moving toward or away from the other.

Experimental Confirmation

While Doppler originally applied his theory to light waves, experimental verification first came with sound waves.

In 1845, Dutch scientist Christophorus Buys Ballot confirmed Doppler’s prediction by placing musicians on a moving train and having stationary observers note the change in pitch as the train approached and then receded. The results matched Doppler’s theoretical prediction exactly.

For light waves, the effect is described using the relativistic Doppler equation, since the speed of light is constant:

where c is the speed of light in a vacuum and v is the relative velocity between source and observer.

This formula is central to astrophysics, allowing scientists to measure the radial velocities of stars and galaxies. For instance, galaxies moving away from Earth exhibit a redshift, evidence for the expanding universe described by Hubble’s Law.

Later Career and Decline

Doppler’s reputation grew, and in 1847 he was appointed Director of the Institute of Physics at the University of Vienna. Unfortunately, his health deteriorated due to tuberculosis, forcing him to move to a milder climate. He died in Venice, Italy, on March 17, 1853, at the age of 49.

Legacy and Modern Applications

Doppler’s principle is one of the most versatile concepts in physics. Its applications span across multiple disciplines:

- Astronomy: Measuring stellar and galactic motion through redshift and blueshift analysis.

- Meteorology: Doppler radar for tracking storms and precipitation.

- Medicine: Doppler ultrasound for blood flow and heart rate monitoring.

- Engineering: Speed detection (police radar) and motion sensing technologies.

His name is memorialized in the Doppler Institute (Prague), the Christian Doppler Laboratory (Austria), and even on the Moon’s crater Doppler and asteroid 3905 Doppler.

Conclusion

Christian Doppler’s 1842 insight unified the concepts of wave propagation and relative motion into one elegant principle. His equation, simple yet powerful, explains phenomena that range from the pitch of a passing siren to the redshift of distant galaxies.

For physics students, the Doppler Effect stands as a reminder of how a single theoretical idea—grounded in mathematics and careful reasoning—can echo across nearly every branch of science.

Leave a comment