Key Points and Summary – USS Jimmy Carter (SSN-23) is the U.S. Navy’s specialized Seawolf-class attack submarine, built with a 100-foot Multi-Mission Platform and precision thrusters to perform delicate undersea tasks while remaining covert.

-The boat provides access and handling for unmanned vehicles, special operations, and seabed work that standard SSNs aren’t optimized to do, yet retains a full attack-sub punch.

-Publicly known history is sparse by design: routine yard periods, deployments, and a few deliberate signals—like a 2017 Jolly Roger return—mark a career lived in the shadows.

-As cables, sensors, and UUVs reshape the maritime fight, Jimmy Carter remains both a useful tool and a blueprint for future SSW-tailored subs.

USS Jimmy Carter: The U.S. Navy’s Quiet Spy Submarine Specialist

Not every undersea job is about stalking an adversary’s ballistic-missile submarine or launching cruise missiles ashore.

Some missions are about access—reaching, sensing, manipulating, and monitoring parts of the ocean that most navies cannot touch.

Those tasks include testing next-generation undersea systems, deploying and recovering unmanned vehicles, supporting special operators, and quietly working around seabed infrastructure that increasingly matters in crisis or war.

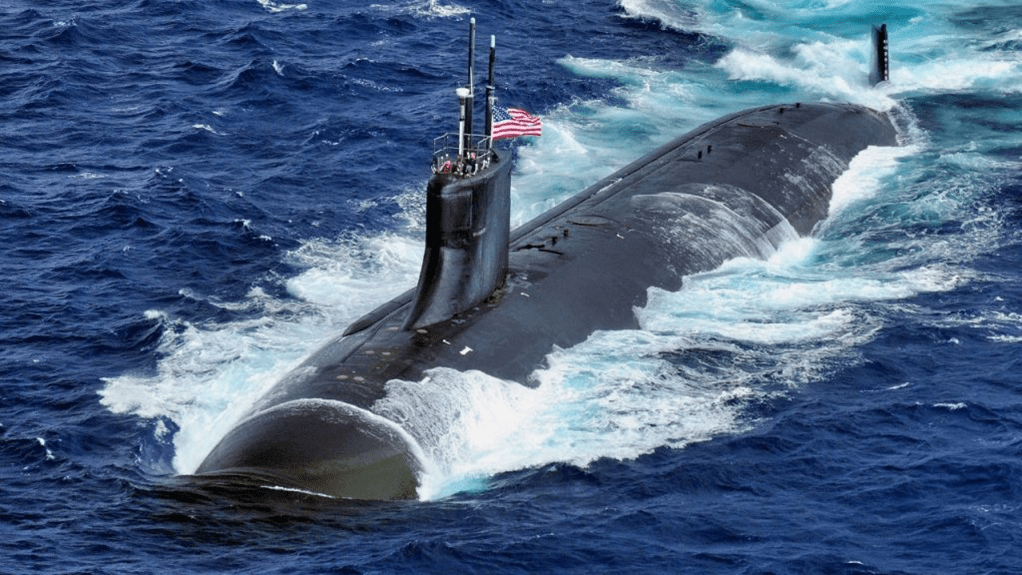

The U.S. Navy built one attack submarine expressly to excel at those jobs: USS Jimmy Carter (SSN-23). She is the third and final boat of the Seawolf class, but she is more than a sibling with a different paint scheme.

Jimmy Carter carries structural changes and handling features that let her act as a special-mission mothership—a platform that can insert people and payloads, hold position with unusual precision, and remain covert while doing so. In an era when undersea cables, sensors, and unmanned systems are strategic targets and tools, the Navy needs a submarine that can operate in the margins—close to the bottom, near complex terrain, and alongside fragile or sensitive equipment—without giving up the stealth, speed, and punch that make an SSN so useful.

USS Jimmy Carter: From Seawolf To “One-Of-One”

The Seawolf design began as the Cold War’s ultimate hunter: big sonar, high speed, and deep magazines to keep up a relentless chase.

When Washington chose to stop at three hulls after the Cold War, the Navy took the opportunity to adapt the third ship, USS Jimmy Carter, during construction. The result was a major hull insertion—a roughly 100-foot segment known as the Multi-Mission Platform (MMP) added amidships.

That plug provides a large, pressure-resistant passage, additional volume, and an ocean interface for swimmers, remotely operated vehicles, and other mission kits. Internally, Jimmy Carter gained the spaces, handling gear, and routing needed to stage and control payloads that don’t fit the usual “torpedo or Tomahawk” mold.

She also received auxiliary maneuvering devices—precision thrusters forward and aft—that allow the boat to hold station or “park” relative to a point on the seafloor or a structure, even in quirky currents. That’s not a parlor trick; it’s how you do delicate work underwater without constantly fighting the boat. Those additions changed more than the silhouette.

They increased overall length to well over 400 feet and raised displacement compared to her two Seawolf sisters. In practice, Jimmy Carter remained every bit an attack submarine—eight 660-mm tubes and a large internal bay for the usual heavyweight weapons—while gaining a mission bay function long before that term became fashionable on surface combatants.

Building A Platform For The Hard Jobs

Submarines live and die by margins—space, weight, power, cooling, acoustic discipline. Jimmy Carter’s modifications were not bolted on; they were designed in so the boat could take on new payloads without compromising stealth. The MMP’s internal access allows sailors to move people and gear across the boat under pressure rather than treat every task like a special-forces launch. The ocean interface is effectively a submerged work door, sized and engineered so divers or vehicles can get out and back safely.

The propulsion and control additions matter just as much. A conventional SSN can hover and back down, but doing fine-grained work near a seafloor object, a sensor string, or a minefield is another level of shiphandling. The extra thrusters and associated controls give the crew the ability to stay still in three dimensions—crucial when sensitive gear must be placed, inspected, or retrieved quietly. None of that capability makes a press release; all of it expands what the Navy can do without sending a surface ship, a diver tender, or an obvious unmanned platform into view.

A Brief History, Mostly In The Shadows

USS Jimmy Carter was laid down in the late 1990s, commissioned in 2005, and homeported in Washington State with the Navy’s Seawolf squadron.

From the outset, the boat belonged to a small community dedicated to developmental and special missions. The command relationships, training cycle, and payload inventory reflect that focus: test new kit, rehearse complex evolutions, deploy when needed, and return without fanfare.

Because so much of this work is classified, the public timeline looks sparse. You will find yard periods for maintenance and upgrades, routine transits to and from San Diego for personnel transfers and component swaps, and the standard drumbeat of Pacific Fleet deployments. What you won’t find are operational details—no annexes about where, when, or how the crew did anything that isn’t meant to be discussed. That opacity is the point. Jimmy Carter is valuable precisely because she can go, do, and vanish.

What We Can Say About Operations (And What We Can’t)

A few items are public because they were meant to be seen—or couldn’t help being seen.

In 2017, Jimmy Carter returned to her home waters flying a Jolly Roger flag, a time-honored submariner signal that a boat completed an operational action. The Navy released photos; the message was subtle and deliberate, but there were no mission specifics. Separately, the Navy has acknowledged that Jimmy Carter earned high-level unit commendation for a past deployment—again, without the narrative that would give away methods, targets, or partners.

Beyond those isolated markers, the boat’s known actions are the ones the Navy chooses to share: scheduled maintenance dockings at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, formal changes of command with the Seawolf squadron at Naval Base Kitsap, and the routine comings and goings that any observant waterfront will notice. Pressed for more, sailors will simply point to the classification stamps. That restraint isn’t coyness; it’s how you keep a tool like this useful.

Why A Single Boat Still Matters

Critics sometimes ask why the Navy fields only one submarine of this type. The answer is that specialization cuts both ways. A heavily modified “one-of-one” is expensive to build and maintain, but it returns value far beyond the steel. Jimmy Carter is a fleet laboratory and a quiet enabler. As a lab, she proves out handling concepts, communications tricks, and payload interfaces for the rest of the force—especially as unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs) grow in size and ambition. As an enabler, she performs the niche missions that do not justify redesigning every attack boat, while informing how future classes should be wired for seabed and special operations work from day one.

Just as importantly, the boat is a deterrent by existence. Adversaries who build seabed sensors, string cables, or rely on undersea infrastructure now have to plan for an American submarine that can reach those places quietly and precisely. That uncertainty complicates their calculus without a single press release.

What “Known” Looks Like: The Boat In The Yard And On The Pier

Because Jimmy Carter disappears for long stretches, the times she appears in public take on outsized meaning. The Navy has highlighted docking availabilities that required novel arrangements to keep other submarine work on track—small signs of a workforce juggling priorities while still giving a unique boat the attention it demands. The Seawolf squadron has quietly marked changes of command on the Olympic Peninsula pier that hosts these rare submarines. And the boat regularly uses Naval Base Point Loma in San Diego for personnel and logistics waypoints, visible to anyone watching the waterfront closely.

These glimpses don’t tell you what she does. They tell you she’s busy—cycling through the maintenance and training that enable operational tasking, and returning home from extended patrols with the same absence of fanfare that marks her departures.

USS Jimmy Carter: The Strategic Logic Only Got Stronger

When Jimmy Carter was conceived, the U.S. undersea community was already thinking beyond classic ASW and strike. Two decades later, the ocean is more wired and more contested. Fiber-optic cables carry commerce and command; seabed sensors feed maritime awareness; offshore energy platforms and pipelines are both targets and dependencies. At the same time, UUVs have matured from small reconnaissance tools to large, long-endurance craft that can shape a fight on their own.

All of that amplifies the value of a submarine that can host, handle, and recover undersea systems while staying covert and self-sufficient. Jimmy Carter’s design anticipated that future: extra volume for gear and operators, a robust interface to the sea, and shiphandling aids that make delicate work feasible. In short, the boat’s rationale aged well.

Where This Goes Next

The Navy is not stopping at one specialized hull forever. Program documents and budget notes now reference a Modified Virginia-class configuration tailored for Subsea and Seabed Warfare (SSW)—a follow-on approach that would move special-mission features into a more repeatable production baseline. That’s less romantic than a one-off, but it’s how you spread capability across the fleet: standardize interfaces, wire in power and cooling, and treat UUVs and seabed work as a routine, fleet-wide competency rather than an exotic edge case.

In that future, Jimmy Carter remains both useful and instructive. Useful, because there will always be missions that prefer a boat and crew with decades of specialized practice. Instructive, because every lesson the crew learned about handling, maintenance, training, and tactics feeds the design of the next boats and the operating concepts that go with them.

Limits, Tradeoffs, And A Realistic Future

No ship does everything. Jimmy Carter’s added length and displacement complicate some maintenance actions and logistics. The unique features demand bespoke parts and highly trained sailors and yard workers. The Navy has to balance the boat’s employment: too secretive and she becomes a boutique asset with brittle availability; too public and she loses the very advantage she exists to provide.

The realistic future is steady work—long deployments with low visibility, periodic yard periods that keep the specialized gear safe and tight, and a measured shift of certain missions to next-generation platforms as they arrive. When that happens, Jimmy Carter can evolve again, emphasizing test and training roles that wring value from a boat whose very structure was built for experimentation.

Bottom Line

USS Jimmy Carter is not a mystery because she hides; she is a mystery because she works. The Navy needed a submarine that could operate where charts and schematics matter as much as sonar plots—a platform that could test, place, recover, and support undersea systems without sacrificing the stealth and reach of an attack boat. By inserting a purpose-built mission bay and giving the crew extraordinary control over the ship’s position in the water, the Navy created a “one-of-one” that has spent two decades doing the kinds of jobs that only get discussed in the barest terms.

That’s as it should be. In a world where seabed infrastructure is a frontline and unmanned systems are multiplying, the quiet specialist has never been more relevant. Jimmy Carter’s value isn’t in the stories we can tell about her.

It’s in the missions we’ll never hear about, and in the next generation of boats and tactics her experience is quietly shaping.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

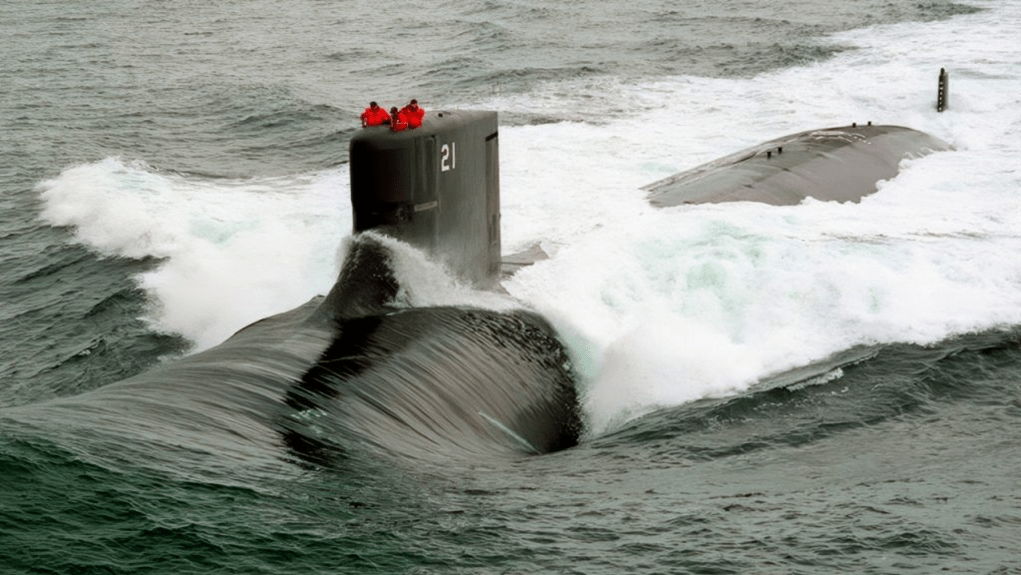

Featured image: The nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Jimmy Carter (SSN 23) sits moored in the magnetic silencing facility at Naval Base Kitsap Bangor in Silverdale, Wash., on Aug. 16, 2006. The Jimmy Carter is the third and final submarine of the Sea Wolf-class. (DoD photo by Master Chief Jerry McLain, U.S. Navy. (Released))

Source: nationalsecurityjournal.org (Published on September 14, 2025)

19 October 2025 at 12:31

A little too much – could have used more opsec.

LikeLike