Featured image: CAPT Prescott Hunt Currier, USN

On 1 June 1939 the Japanese Navy introduced a new type of numerical code referred to by Navy COMINT personnel as AN, JN-25 or the Operations Code. This code used a vast number of “additives” (or subtractor) keys, similar to the [redacted] used by the U.S. [redacted] Navies from 1941 through 1943. Mrs. Driscoll and Mr. Currier spear-headed the attack and we were soon [redacted] reconstructing the code. Recovery of the additive keys, however, involved much more labor and required many more crypto-personnel than the earlier transposition keys. Main work of solution was undertaken at Washington. By December 1940 we were working on two systems of keys used with this code book: the “old” keys for code recovery and the “new” keys for current information. In the spring of 1941, the U.S. COMINT Unit at Corregidor polled its effort with [redacted]. The [redacted] had also reconstructed this Japanese Number Code to a partially readable extent and wre busy recovering keys and “filling in the blanks” in the code.

Upon CINCAF’s recommendation, the U.S. Asiatic COMINT Unit was authored [redacted] of this system, and a set of “code-values,” cipher keys, skeleton code-book, cryptanalytical techniques, etc., intended for Pearl Harbor were diverted to Corregidor. A replacement was hastily prepared in Washington and sent to Pearl Harbor, arriving in November 1941. On 10 December 1941 the Pearl Harbor COMINT Unit discontinued attack on the Japanese Flag Officers’ Cipher and concentrated all effort on the “Numbers System”. (Incidentally, we never solved the Flag Officers’ Cipher and the Japanese discontinued its use, probably because of its slowness, complexity, and susceptibility to error. It was the only Japanese Naval Cryptographic system which the U.S. Navy ever failed to solve.)

On 1 December 1941, the numbers system became unreadable, CINCAF promptly advised Washington to this effect. This could have been a tip-off as to coming hostilities, but it also could have been merely a routine change of system. After all, the code had been in use for two and one‑half years. Two weeks later Corregidor flashed the good news that new keys were being used with it. 6 This was the third or fourth set of keys used with this same code book. By February 1942, the new keys had been solved to a readable extent. This same code was retained in use through the Battle of Coral Sea and the “build up” for the Battle of Midway. It was finally superseded on 31 May/1June 1941 by a similar code. If (and it is a big if), if the Japanese Navy had changed the code‑book along with the cipher keys on 1 December 1941, there is no telling how badly the war in the Pacific would have gone for Australia and the U.S. or how well for the Japanese in the middle stages. Without detracting in anyway from the cryptanalysts who spotted the actual tip‑offs or from the men who did the fighting, due credit for Coral Sea and Midway should be given to the Navy’s pre‑Pearl Harbor COMINT effort.

The decryption of Japanese Diplomatic messages in Washington throughout 1941 is now a matter of public knowledge in some forty volumes of official records. We may summarize by stating that COMINT organizations of the Army and the Navy worked in perfect coordination during this period and provided the White House, State Department, Army General Staff and Naval Operations with authentic, timely and complete information concerning the Diplomatic Crisis and the mobilization and movements of Japanese amphibious forces for the conquest of Southeast Asia. The White House and State Department used this information with consummate skill. The failure of the General Staff and Naval Operations to profit from the same information 7 is beyond the scope of this “History”.

So long as the Navy did all the interception and the Army relied on “back‑door‑methods” for its source of messages there was no problem about “collaboration” or “division of effort” in interception. But troubles arose when the European War broke out and the Signal Corps began to establish intercept units at Army posts. The Signal Corps officers responsible for the Army Intercept Service were strong on theory but weak on performance and unwilling to profit by the greater experience of the Navy. Coordination and consultation were considered by them to be more important than getting on with the job. Weeks were wasted in fruitless conferences while the Signal Corps learned “the hard way” and saw their pretty theories demolished by disagreeable facts. In 1940‑41 the Army had no intercept stations which could match the Navy’s “big five”: Corregidor Island, Philippines; Bainbridge Island, Washington; Cheltenham, Maryland and two others with their directional antennasbeamed on the “target” transmitters, diversity receivers to overcome selective fading, syphon records for copying high speed automatic transmissions, highly trained operators, and experienced supervisors. Allocation of intercept effort was finally settled on a trial‑and‑error basis. The Signal Corps covered such of the International Commercial Transmitting Stations as it could; the Navy covered the others as a matter of necessity. Theoretically it was bad to “split” a circuit: practically there was no alternative. Assignments were changed almost weekly as radio propagation suffered seasonal changes, as more operators and more receiving equipment became available, and as the pressure from higher authority required speeding up delivery and “bridging the gaps” in intercept traffic regardless of cost.

Covering international radio circuits is like fishing with a dragnet, anything and everything comes in with the haul. Then it is necessary to sort out the catch and discard what is not wanted. Monitoring for Japanese diplomatic traffic automatically gave naval attaché messages, German diplomatic and much more.

It is needless to review all the arguments and discussions that took place in 1940. Not only did intercept assignments between the services change from time to time during 1940 and 1941, but the assignments to intercept stations within each service changed from time to time. For example, we eventually found we could get the best coverage of the Berlin‑Tokyo circuit at Corregidor; messages in the “Purple” system were therefore re‑enciphered in a Navy system and forwarded to Washington by radio. During the last few weeks before the Pearl Harbor attack, while U.S.‑Japanese relations were at a crisis, Japanese diplomatic messages intercepted at Bainbridge Island, Washington, Cheltenham, Maryland and another station were relayed to Washington by landline teletype. Army intercepts continued to come in by mail after 7 December 1941. The Navy also arranged for “back‑door” services on all diplomatic traffic in and out of Washington and New York ‑ to back up the radio intercept stations.

The squabbles between the Army and the Navy COMINT organizations were confined to the interception, “processing”, translation and dissemination of Japanese diplomatic messages. These controversies settled themselves in the course of time, and in retrospect are seen to have been merely petty annoyances. [redacted]. In the Japanese diplomatic traffic the Navy found it had a bear by the tail and couldn’t let go until after the attack on Pearl Harbor when Japanese diplomatic messages became greatly reduced in volume and importance. Then the Army was able to handle all Japanese diplomatic decryption and translation unaided, leaving the Navy free to undertake a serious attack on German submarine communications.

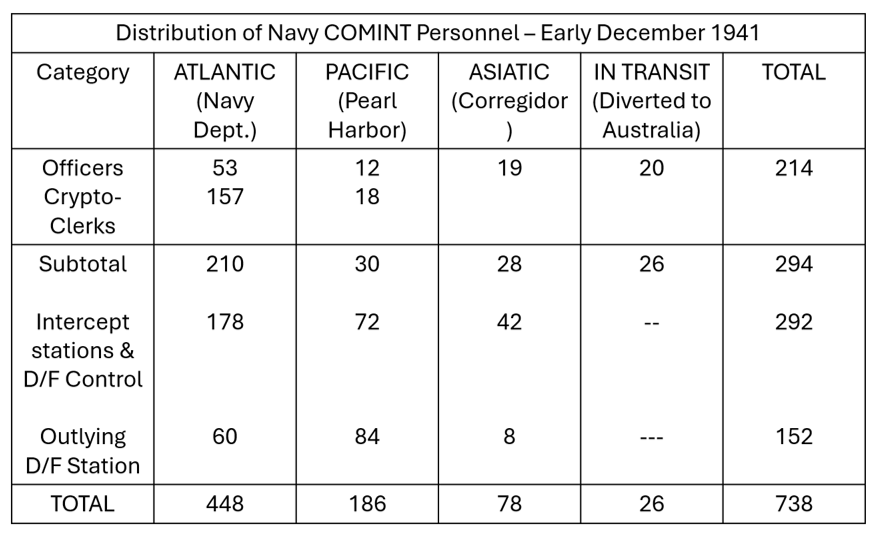

During November and early December of 1941, Japanese diplomatic traffic was diverting 30% of the Navy’s intercept and D/F effort, 12% of its decrypting effort and 50% of its Japanese translation effort from their proper military functions. Loss of the translators hurt us the worst as the total number available was inadequate even for Japanese Naval messages. Loss of decryption personnel was more serious than the numbers indicate because our “first team” in Washington had to be assigned Japanese diplomatic traffic. Detailed breakdowns are given in tabular form following:

Source: SRH-149

Leave a comment