By John Brady

In the fall of 1948, after three years in the Navy, I received orders to Cheltenham, Maryland where I became acquainted with the acronym SESP, short for “Special Electronic Search Project.” Before reporting to Cheltenham, we were put up in temporary buildings at West Potomac Park, right behind the Lincoln Memorial. This was a New Navy to me. There were no fences, no marine guards, you could go “ashore” any time you liked and there were no watches.

Unfortunately the time it took to process us was short and I soon found myself at Cheltenham, where there were fences and marine guards. In fact, there were fences surrounding portions of the base already behind a fence. At Cheltenham we attended a school run by a LT Ritchie; I think we were the second class. Things were not very well organized and a lot of the equipment was not working or in some cases not installed. Between lectures on signal characteristics, frequencies and usage we did a lot of maintenance and installation. This lasted for a couple of months and included at least one trip behind the inner fence. Finally we got our orders, everyone went to Communications Unit 32. CU-32 was divided into several surface-ship units, one submarine unit and one airborne unit. I was assigned to the airborne unit which was a detachment of Patrol Squadron 26 (VP-26) stationed at Port Lyauty, French Morocco.

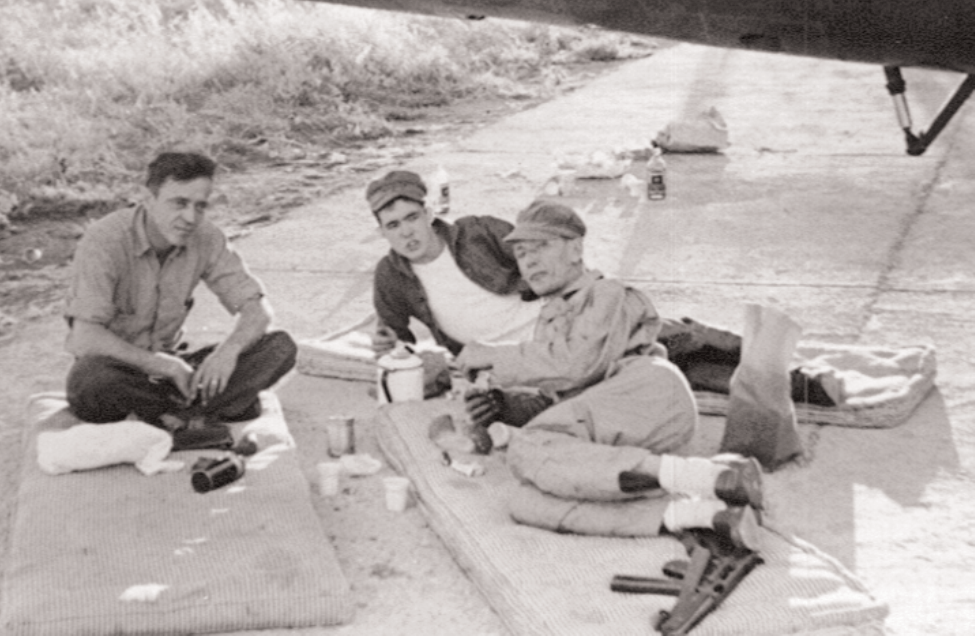

Plane Guards – Note the .45 Thompson Sub Machine Gun

My first flight ever was from Washington, D.C. to Westover, Massachusetts, on a MATS (Military Air Transport Service) plane that had real reclining seats just like one might find on a train. It was a long time before I flew on a plane with reclining seats again. The plane blew a tire landing at Westover, but it didn’t seem like a big deal; there were a lot of sparks and they brought a bus out to the plane to take us to the terminal. I thought it was just part of flying. The rest of the trip to Port Lyauty was uneventful. My new home was an airfield shared with the French who flew several World War II wood and fabric patrol planes. The first thing I saw as we taxied to a parking spot was a runway repair wagon manned by robed Arabs and drawn by a camel and a donkey hitched together. Not the way it was done back in my home town of Waukegan. The second thing I saw was a PB4Y-2 with a broken landing strut in the grass.

Our unit’s office was a Quonset Hut as was our living quarters. We also had a shop on the top of the main hangar where we did our maintenance and equipment check-out. The VP-26 detachment consisted of 4 planes (not counting the broken one out in the field). I spent the first few weeks getting checked out on the equipment we had on the planes, but did not fly because the authorization to pay me flight pay had not been approved. During this period one of the PB4Y-2s experienced a broken elevator trim-tab cable shortly after takeoff, which resulted in the plane being uncontrollable. The skin and flesh were rubbed off the pilots’ hands as a result of their efforts to control the plane. All hands bailed out and landed successfully. I could see the unmanned plane circling, then nose over and head for the ground. There was no fire but debris, including mail, was scattered over a wide area. One of our missions was to deliver mail to various embassies. There seemed to be an endless supply of PB4Y-2s because a replacement showed up shortly after. That made 2 down out of 4 and I had yet to make a flight.

The attached picture are three P4M-1Q Mercators from the Naval Air Facility Port Lyautey, Morocco, in bogus markings meant to confuse intelligence gatheres. The aircraft flew as part of Naval

Communications Unit 32G. The inscription on photo reads: To “Uncle Bill” Lockert, so that he may have some appreciation for what it was like in the “Good Old Days.” Signed: G.P. March “The Grey

Eagle”

Eventually my flight status was established and I started flying. Actual missions consisted of data collection around the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Adriatic Sea and along the border separating Europe and the USSR. To test our equipment we also flew locally when the planes were being tested after maintenance and for pilot Ground Control Approach proficiency. Occasionally we practiced shooting at smoke flares to make sure everything was in working order. Shooting at flares could result in flying into bullets bouncing off the water, or if an interlock failed or was not set properly, hitting the tail of the plane. A favorite trick was to turn off the power to an occupied waist turret. The occupant would then end up almost upside down, a position from which it was hard to see the plane. A typical mission might last for a week, requiring overnight stays at places such as Rome, Athens, Istanbul, Malta, Cyprus, Wiesbaden, London, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Oslo, Munich and once Vienna. The stay at Vienna was the result of taking Admiral King there for a conference. Extended flights might require a 30-hour maintenance check away from home, which took a day for all hands to complete. Occasionally mechanical problems would require layovers until parts were flown in. Our planes were never left unattended overnight. Two or three crew members stayed with the plane, sleeping in sleeping bags aboard or on the ground and cooking meals on the electric stove which was also used to cook meals in flight.

Initially our equipment was installed on the flight deck in the space resulting from the removal of the foreword top turret. The crew would consist of a pilot, copilot, navigator, plane captain (usually a Chief aircraft mechanic), mechanics, ordinance men, radiomen and three CU-32 personnel (usually 2 enlisted and an officer) for a total of about 14. The extra mechanics and ordinance men were carried to man the 5 turrets. A lot of time was spent going to and from the area we could expect to collect any electronic signals (ELINT), so for about half of each flight we CU-32 personnel had little to do. Circumstances permitting, we could man the search radar, play Acey-Duecy with the radio man, or even sit in the pilot’s seat and tweak the autopilot. There were long periods of boredom and some exciting moments. Generally we flew below 10,000 feet which meant flying thru a lot of turbulence; once we were hit by lightening. Weather caused other problems. There was a Yagi antenna mounted on top of the fuselage where the foreword turret used to be that would ice up add break off, sometimes impaling itself in the tail. Icing was frequently a problem on the wings and the propellers. When the props were deiced, the ice would hit the fuselage with loud bangs and chip off the paint.

One time, flying from Rome to Athens, which should have been short and easy flight, we encountered headwinds that brought our ground speed down to less than 100 kts and forced us to land at a Greek air base near the Corinth canal. We were treated to a hot meal in their mess hall that included a glass of wine and a toast to Queen Frederica followed by a real bed for the night. The next day was dry and sunny, but going from the parking area to the runway the starboard wheel went thru the surface of the taxi way. It took several trucks and a lot of shoveling to get it back on top.

Sometimes it wasn’t the weather that was the problem. Once, in Athens, our alert plane captain caught the civilian fueling crew trying to put toilet paper in our gas tank by shoving the paper up the fuel hose nozzle. After that we strained all the fuel, at civilian airports, thru a chamois. Another time, leaving

Stockholm, we took off without a gas tank cap on one of the wing tanks (our fault). When we got airborne a large stream of aviation gasoline shot out of the tank and moved aft along the wing and mixed with the engine exhaust. It was decided not to shut down the engine fearing a backfire that might ignite the gas. The pilots managed to circle and land without any problems. The gas cap was found on the ground when we went back to top off the tanks.

Wiesbaden, Germany was a frequent destination. We would fly there from Port Lyauty, spend the night, then fly over the Baltic Sea within line-of-sight of the coast, returning to Wiesbaden. Liberty in Wiesbaden was enjoyed by all mainly because of the good shopping. Things like cameras, cuckoo clocks and even long-haired Daschund puppies were brought back to Port Lyauty for folks on the base. Near Easter of 1950, one such flight over the Baltic went missing and was presumed to have been shot down by Soviet fighters. We were told that parts of the plane were recovered with bullet holes but that no bodies were recovered. An evaluator and an enlisted man from CU-32 were aboard, but I don’t remember their names. This was a shock because even though we knew there was some danger in what we were doing, there had been times when Soviet planes would come up and take a look at us but did not appear hostile. I once took photos of a YAK fighter doing just that along the European/USSR border. My film was confiscated and I never saw the pictures. Back at Port Lyauty very little was said about the shoot-down and no one I knew back in the states ever mentioned it. I did see a very short article in either a News Week or Time magazine. There was no memorial service on the base recognizing the loss of this plane. Shortly after this incident, I went back to Pautuxet, Maryland to pick up one of the newly equipped planes. The aft top turret and two waist turrets were removed and the ELINT equipment consisting of 4 operating positions and an evaluator position were installed. Each plane now carried 4 enlisted operators and 1 officer evaluator from CU-32.

The next year passed without any serious problems. Then, on 7 March 1951, one of our planes headed to Rome experienced the failure of three engines. It is my recollection that the problem was carburetor icing as the result of broken alternate-air door actuator arms. I can remember having to get one of these broken arms welded on a previous flight and helping the Plane Captain install it during a layover at Rome. Six of the fourteen man crew survived; one with a broken back. Bob Warner from CU-32 survived, but Russel Aiken, new to CU-32, was lost. I still have one of the programs from the memorial service on the base that lists the missing crew members. Other planes from the detachment went to Rome to search for survivors and eventually for debris. Two of us had a minor incident while walking the beach near Anzio looking for debris and/or any classified material. We walked thru a gate in a chain-link fence that was open to let sheep graze in this fenced-in area and continued along the beach. After a while we noticed ammunition bunkers inland from us which should have been clue that maybe we were trespassing. To make a long story short; some Italian soldiers in a Jeep picked us up and put us in jail. It was well after dark before someone from the embassy got us out.

My tour at Port Lyauty ended that same month. Believing that flying out of Sangley Point in the Philippines would let me visit lots of new cities in the far-east, I volunteered for duty with CU-38 and was accepted. Not only did I get a new location, I also got a new aircraft to travel in. The P4M was as new as the PB4Y-2 was old, it was designed to be photo-reconnaissance plane thus the name “Mercator.” I think that the fate of Gary Powers lead to the P4M’s change of mission. It had two engine nacelles, each housed a Pratt and Whitney 4360 radial engine and a jet engine. Both engines burned aviation gasoline and, when the jets were used the gas tanks emptied at an alarming rate. Except for takeoffs, landings and bursts of speed the jets were not used. There were a few problems; the propellers would occasionally stick in reverse and the primary electrical power was from alternators and the selenium rectifiers that converted the AC power to DC were prone to failure. These rectifiers were located in the wings as were the fuel tanks. Rectifier failures usually resulted in smoke and as everyone knows “where there is smoke there is fire;” this would generate concern when in the air. This plane had a bow turret with twin 20 mm guns, a top turret with twin .50 caliber guns and two 20 mm guns in the tail. The bow turret initially spewed the spent brass shells overboard; but they would sometimes hit the propellers so the turret was modified to eject the brass to the inside of the turret where it would accumulate about the gunners feet. Firing the bow turret was not fun, you had to wear your oxygen mask because of the smoke and fumes and your feet got roasted. This turret was prone to jamming, which in a way solved these problems. It was generally accepted that the important guns were the ones pointing aft, and this proved to be the case for the plane I flew in. But I get ahead of myself.

We CU-38 personnel joined the P4M aircraft at NAS Miramar, not far from San Diego. We flew with the aircrews as they trained in these new planes. Everyone went to gunnery school at North Island and gunnery practice at Boarder Field where we shot at tow targets from aircraft turrets mounted on trucks. We deployed to Sangley Point in the fall of 1953 and were put up in Quonset huts, just like Port Lyauty, and started our patrols. We spent a lot of time flying up and down the Formosa Straits with particular attention to the islands of Quemoy and Matsu, and an occasional check of Hainan Island to the south. Sometimes we would go to NAS Atsugi, near Tokyo Japan, or Okinawa and make local flights (leave from and return to the same place) along the coast of China. On one such flight we were attacked by and exchanged fire with two MIG aircraft. Our pre-planned exit strategy, head away from the coast and dive to about 100’ off the water using the jet engines for maximum speed was implemented. Our pilots, Richard Renner and Melvin Davidow got us safely to Atsugi and all hands were awarded an Air Metal. LT Melvin Davidow keeps in contact with many of the “Special Project” personnel and plans to write a book on his times at Sangley. He also contributes to the many “VQ” web sites that chronicle P4M “events.”

Flying in the Far East did not get us to any civilian airports in exotic cities with stays in fancy hotels such as we experienced in Europe; all we saw were military bases that were crowded with planes engaged in the Korean war. Unlike Port Lyauty, we were not allowed to take pictures from or of the planes.

Once, coming into Okinawa unannounced, we were met by two USAF jets sent up to identify what they thought might be an unfriendly aircraft; and once we dove down thru the clouds to identify a radar target in the Formosa Straits and found a US destroyer with many guns tracking us. One interesting experience was a flight on a USAF B-50 configured for ELINT collection. They flew to Sangley Point and we CU-38 operators switched with their AFSS counterparts. The B-50 was not as comfortable as our P4M; for example, the tail gunner took his box lunch and propelled himself down a “tube” to his position where he had to stay while the plane was pressurized. All the air force operators were officers. I liked the Navy way of doing things a lot better. About June of 1953, I responded to a call for volunteers for TAD on the USS BECUNA (SS-339). The reward was that the volunteer would get his choice of duty station when the trip was over. I also made Chief at the same time, coming very close to being a single hash mark chief.

My plan was to ask for another tour at Sangley Point, so I left my car and all my civilian clothes behind and took off for Cedar Rapids, Iowa to learn about the BLR-1. The BLR-1 was electrically very similar to the APR-9 we were used to, but very different physically. The next stop was 3801 Nebraska Ave. for more training, then to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard and the USS BECUNA where I met the second NSG operator Carol Linebough (if my memory is correct), The two of us would stand “watch on watch” while on station. The BECUNA was World War II fleet boat that was in the yard to have a snorkel installed, Aside from getting our equipment installed and running, we had little to do. Our next stop was New London, Connecticut to get provisions, then to Scotland underwater the entire trip, submerged during the day and snorkeling at night. We stood fifteen minute periscope watches while snorkeling. It seemed like fifteen minutes lasted for hours, and when it was clear every star breaking the horizon looked like a ship. Our data collection trip was uneventful and when it was over, it was back to 3801 Nebraska Ave. by air with a stop in London. After our debriefing, I expected to go back to Sangley Point but I was told returning was not an option and I got orders to the Navy Computing Machine Laboratory in St. Paul Minnesota. By this time my burning desire to return to Sangley Point had cooled to the point that my car and civvies did not seem like a great loss. The P4M that I had flown in at Sangley Point was shot down in August of 1956 with the loss of the entire crew including W.F. Haskins of CU-38. We were on the same crew almost all the time I was at Sangley. The guy that sent me to St Paul did me a favor without knowing it. My ELINT reconnaissance career was over except for a trip on the USS GUDGEON (SS-567) when I subbed (pardon the pun) for a friend of mine in 1957.

Looking back, being in “Harms Way” probably was true, but at the time we didn’t think about that. We just did our jobs, had a good time, made a lot of good friends, and looked forward to retirement and the good life.

Source: NCVA CRYPTOLOG, Summer 2005

7 August 2025 at 11:20

Amazing to hear stories of pioneers in our business. Thank you Chief Brady.

CTRCS(NAC) Ret.

LikeLike

7 August 2025 at 19:57

What a great story, many thanks for sharing.

LikeLike