by Michael Fredholm, Association of Former Intelligence Officers

In 1946, Sweden had not yet chosen sides in the emerging Cold War. Leading members of the Swedish Social Democrat government, primarily the powerful Foreign Minister Östen Undén, distrusted the Western democracies and regarded the Soviet Union as a viable protector.

Swedish intelligence had cooperated with its Western counterparts during the Second World War. After the war American intelligence was represented in Sweden by a Strategic Services Unit (SSU), whose Chief of Station in Stockholm was Charles E. Higdon. In August 1946, when the American intelligence chiefs discussed cooperation with the European countries, they were not yet sure of which side Sweden would choose, West or East: “They will either want to work with us or with the Russians,” one of them concluded.1

By 1952 secret verbal and written agreements between the United States and Sweden had put a covert relationship on a firm basis. Henceforth, Swedish intelligence, and the Swedish military, would cooperate with their U.S. counterparts “on the same basis as other nations whose ability to defend themselves is important to the security of the United States,” as the Truman administration put it.2 Sweden had chosen to position itself in parity with the NATO countries, although for reasons of domestic policy it wished to keep the agreements secret.

What had changed? Swedish Prime Minister Tage Erlander was concerned about what was happening in Eastern Europe; however, the Swedish media and the foreign ministry under Undén trusted the Soviet news reporting, which presented a rosy picture of the situation. Then came the Polish elections of 1947. This time, the Swedish national SIGINT service, the National Defense Radio Establishment (Försvarets radioanstalt, FRA) reported directly to Prime Minister Erlander about the election results. Erlander noted in his diary: “The election methods were exposed with terrible exactness—‘investigate so that they do not hide an opposition ballot up their shirtsleeves.’ So this is the nice election which even our press was duped into believing in.”3 Based on the SIGINT reporting, Erlander decided to turn his government towards the Western democracies, not the Soviet Union.

SIGINT Exposes Election Manipulation

The difficulties of learning firsthand what took place behind the Iron Curtain became particularly obvious during the Polish elections in 1946 and 1947.4 First came the Polish people’s referendum on 30 June 1946 on the abolition of the Senate, the new economic system, and the territorial demands of the new Poland. The pro-communist block demanded a resounding ‘yes’ to all three questions, hence the popular name of the ‘Three Times Yes’ referendum, which was seen as a means of deciding whether the Polish electorate supported or opposed communism. However, the communists already controlled much of the government, including the Polish army, police, and the security service.5 By these means, the referendum results were manipulated. Official results, as reported by the Soviet newspaper Pravda, gave the impression of being a resounding victory for the communist bloc.6

For the Swedish political leadership, there was no way of knowing how the election had been carried out based on news reports and diplomatic reporting alone. Fortunately, there was still SIGINT collection. The FRA had monitored Polish encrypted military communications at the time. These intercepts offered a completely different picture of the referendum results. The intercepts showed that in reality, it was only the question of territorial demands that had received a ‘yes’ vote. In addition, the FRA reported that the referendum officials in the district were ordered “not to communicate” the results. The pro-communist block had accordingly lost the election, yet it had managed to manipulate the result so that the world believed it decisively had won the support of the Polish electorate.

Similar events, and news media assessments, followed during the Polish parliamentary elections held on 19 January 1947. Again, the election results were manipulated, yet again the FRA reporting was able to present the realities of the elections. Voters suffered intimidation and violence if they persisted in voting for the wrong candidates.7

The Swedish press had, if anything, again followed the Soviet line. The press, for instance, reported that the Polish security service had found a combat order from the Polish anti-communist underground on how the elections would be sabotaged. It also mentioned that several members of the local election committees and security personnel had been assassinated, implicitly by the Polish underground opposition.8 The voter intimidation and election irregularities went completely unreported by the press.

Sweden Turns toward the West

What was Prime Minister Erlander to believe? Four days after the elections, FRA representatives met Erlander to brief him on their findings. This briefing and subsequent reporting, enabled Erlander to assess the real situation of politics in Soviet-controlled Poland and Eastern Europe, and to base policies on fact, not on newspaper reporting.

The FRA reporting was an eye-opener that greatly influenced Erlander in his understanding of events in Poland and elsewhere in Soviet-held Europe. SIGINT reporting was the only source on the real election results available at the time. Moreover, the briefing was the first in the series of events that came to influence Swedish foreign policy (the communist coup d’état in Czechoslovakia in February 1948 and the ominous Soviet invitation to Finland in the same month to sign a treaty, in effect a means for the Soviet Union to base troops in Finland).

However, Prime Minister Erlander had to share political power with other influential Social Democrats, including Foreign Minister Undén, who were more inclined than Erlander to accept Soviet demands.

Undén was not averse to clandestine cooperation with the West; he simply did not want it to be known to the public. So, while Erlander encouraged Swedish intelligence to increase cooperation with its Western counterparts, and collaboration grew, Sweden’s foreign policy remained focused on what Erlander realized was the illusory safety of non-alignment and neutrality.9

By the end of 1951, Erlander had succeeded in gaining the acceptance by the United States of the Swedish posture. A major reason for this was that intelligence cooperation then was highly successful.

In early 1952, President Harry Truman concluded that “as a means of increasing the already substantial cooperation that Sweden is in fact giving us, the United States should receive sympathetically such requests for assistance as Sweden makes … on the same basis as other nations whose ability to defend themselves is important to the security of the United States.”10

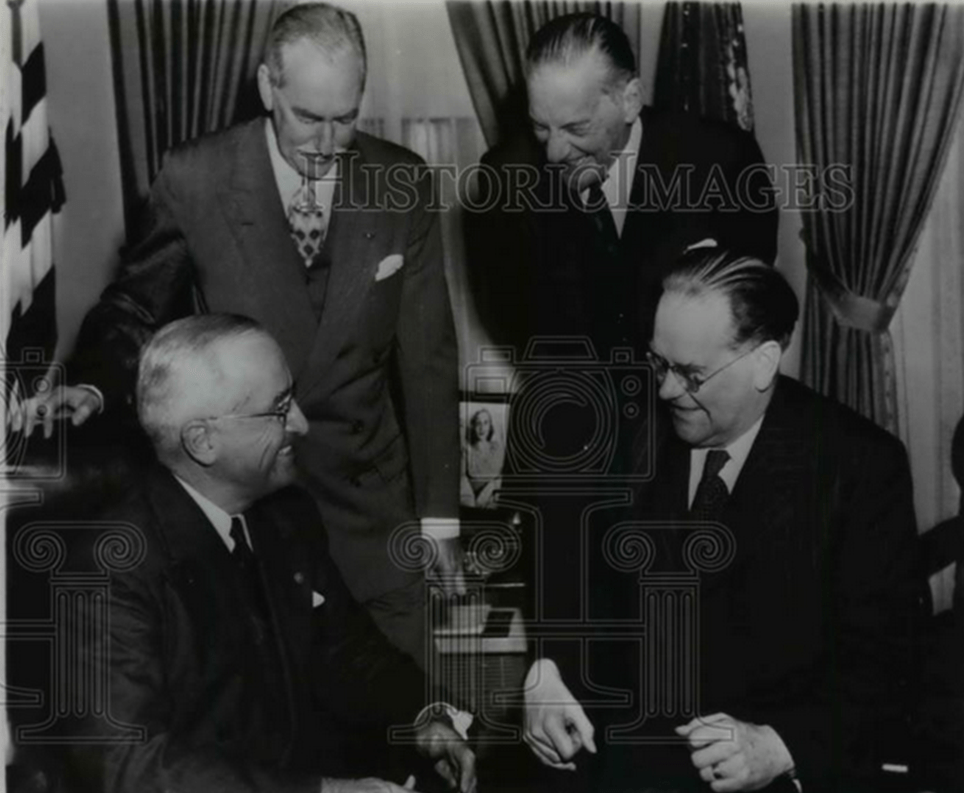

On 14 April 1952, Erlander visited Truman.11 In a top secret memorandum for the President, Secretary of State Dean Acheson explained the situation: “United States relations with Sweden are strongly influenced under present circumstances by that country’s determination to avoid involvement in any military bloc or alliance. Nevertheless, there is an official Swedish desire, even in matters involving East-West tension, for inconspicuous or covert cooperation with Western countries, up to the point where there is danger of such cooperation becoming generally known.”12

A formal agreement was negotiated in late June 1952. On 2 July, the head of the Swedish Defense Staff, Richard Åkerman, wrote in his diary: “We have through clever choice of words agreed on terms that put us in parity with the NATO countries. This may absolutely not be released to the public, because then the Soviets will be found to be right in their assessment that Erlander was there for this purpose.”13

1. OIC to FBL, Memorandum, Miscellaneous Comments and Observations during European Trip, 30 August 1946 (TOP SECRET CONTROL). Declassified. With thanks to Cees Wiebes.

2. U.S. National Security Council, Statement of Policy proposed by the National Security Council on the Position of the United States with Respect to Scandinavia and Finland, NSC 121 (TOP SECRET), 8 January 1952. Declassified in its entirety and available from the National Archives and, with parts redacted, from the Office of the Historian, Department of State. Approved by President Truman on 17 January 1952.

3. Tage Erlander, Dagböcker 1945-1949 (Hedemora: Gidlunds, 2001), 160-161. Translation from the original Swedish.

4. Based on Michael Fredholm, “Trust, but Verify: The Verification Role of Signals Intelligence—Then for Decision-makers, Now for Historians,” Need to Know IV: What We Know about Secret Services in the Cold War – A State of Affairs 25 Years after 1989, International Conference, Leuven, 23-24 October 2014.

5. The Red Army’s Northern Group of Forces, totaling some quarter-million soldiers, was stationed in Poland after the war.

6. Pravda, 13 July 1946, p.4.

7. The FRA reporting was based on telegrams from the Internal Security Corps (Korpus Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego, KBW) under the Polish Ministry of Public Security. These telegrams instructed the security troops to search the shirt-sleeves of the voters so that they did not hide opposition ballots there. Several people who advocated opposition parties were arrested. Election officials simply disregarded the votes for the opposition when they reported in the final results, even though this meant that up to 85 per cent of the votes were ignored.

8. Dagens Nyheter, 19 January 1947, p.16.

9. For instance, Erlander knew that from 1943 to 1945, British and American bombers had regularly overflown Sweden on their way to targets in Germany. Since the German air force by then had lost its power to strike back at Swedish territory, Sweden had quietly accepted the Allied overflights and had not attempted to oppose them. In the early years of the Cold War, it was obvious that in case of a new war, American bombers would again fly through Swedish airspace, but this time on their way to bomb Soviet targets. However, the Soviets were in a far better position to retaliate than had been the Germans, and any retaliation would likely strike Sweden, too. Thus, neutrality was no real option, only a political posture in times of peace.

10. U.S. National Security Council, Statement of Policy, NSC 121.

11. Memorandum of Conversation, by the Secretary of State, Washington,

14 April 1952 (SECRET). Declassified and available from the Office of the Historian, Department of State. The original in Harry S. Truman Presidential Museum / Truman Library.

12. Memorandum for the President, Visit of Prime Minister Erlander of Sweden, Department of State, Washington, 11 April 1952 (TOP SECRET). Declassified and available from Harry S. Truman Presidential Museum / Truman Library.

13. Wilhelm Agrell, Fred och fruktan: Sveriges säkerhetspolitiska historia 1918-2000 (Lund: Historiska Media, 2000), 151. Translation from the Swedish original.

Leave a comment